Denis Esakov & Karina Diemer

Moscow from the Air

Denis Esakov, Karina Diemer

23. d’agost 2017

Adjaye Associates: Moscow School of Management, 2010 (Photo: Denis Esakov)

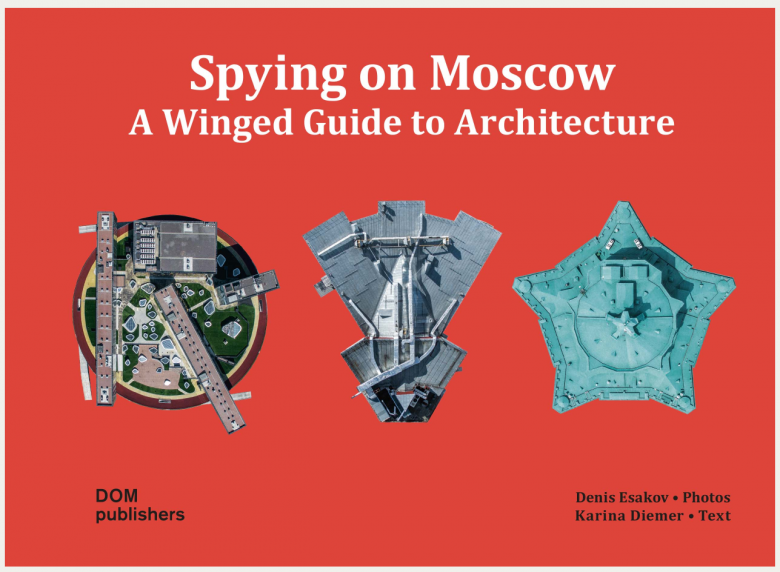

Spying on Moscow is a new "winged guide" by photographer Denis Esakov and author Karina Diemer that portrays Russia's largest city from above to reveal the "fifth façades" of its important buildings.

With Google Maps offering aerial photography on demand, the drones-eye views in Spying on Moscow: A Winged Guide to Architecture are not entirely novel. But Denis Esakov goes beyond the grainy aerials offered online with his carefully composed, crystal clear aerials that are accompanied by low-level and street-level views for broader coverage of such buildings as David Adjaye's Moscow School of Management. Additionally, his use of drones – one of this century's primary means of surveillance – taps into the historical lineage of spying and makes his subject, Moscow, entirely appropriate.

Here we present some of Esakov's photos and Diemer's text from Spying on Moscow, published this year by Berlin's DOM Publishers.

Adjaye Associates: Moscow School of Management, 2010 (Photo: Denis Esakov)

A pedestrian in the city sees buildings in the context of the city landscape, with the façades as main attraction. Architects and engineers are focused on construction and design, and urbanists consider individual buildings solely as elements of the city complex. Thus the angle of observation influences the reception of the objects: viewing from above, onto the "fifth façade" that barely anyone sees, opens completely different dimensions.

The Moscow photographer, Denis Esakov, has captured the fifth façades of Europe's largest metropolis with a remote-controlled drone: roofs, domes, towering building cubes. In this small bibliographic picture book, Spying on Moscow: A Winged Guide To Architecture, the photographer portrays over 70 architecturally important objects from the past hundred years. This is the first book ever to use photos taken from a drone, flying over Moscow. Denis Esakov tells a short story about each building with three pictures; two are taken from above and the third is taken from the perspective of an observer at ground-level. Thus composing a three-dimensional overall impression, enabling us to see the sights of the city with a new point of view – just like looking at an architect's model. Such a view helps to develop perception and captures the essence of the building from three angles. The hyperbolic construction of the Shukhov Radiotower (1922) reminds us of a bird's nest; the former residential Government Building (1928-1931) by Boris Iofan reveals a complex composition with different volumes and courtyards; the Red Army Theatre (1934- 1940) – that should be recognizable from above – develops into the emblematic five-pointed star.

Moscow State Palace of Child and Youth Creativity, 1962 (Photo: Denis Esakov)

Moscow’s Fifth Façade

Passersby see a building in the context of its architectural setting, but focus their attention on its façade. Architects and engineers perceive buildings through the prism of their professions, putting the emphasis on load-bearing structure and layout. Urbanists conceive of individual buildings as elements of an urban ensemble. The architectural photographer, meanwhile, may photograph a building from the point of view of any of the above – and still has other options. Like a talented actor, this kind of photographer is capable of taking on the guise of a casual passerby or of becoming an artist (whether an abstract artist or a strict realist).

Denis Esakov’s Fifth Façade series is strong on rationalism, but also contains an emotional aspect, which gives us a feeling of soaring above the city and reveals a new aesthetic

, what until this point has struck us as familiar or absolutely ordinary. Balancing on the border between documentary and artistic architectural photography, Esakov manages to create works in the spirit of "straight photography" which combine originality of format and maximum accuracy of depiction.

Moscow State Palace of Child and Youth Creativity, 1962 (Photo: Denis Esakov)

The increasingly popular technique of drone photography gives us the ability to fly over familiar buildings and see them from above, exposing to us the fifth façade which is usually concealed from our eyes. Until recently, it was only architects and their clients who had the opportunity to examine models of buildings and see them from all sides. Now technology enables the possessor of the "winged guide" to see Moscow’s sights from the architect’s point of view. In his Fifth Façade series Esakov does not try to pick out individual parts of a building; what interests him is the building as a whole. Rejecting purely artistic effects, decorativeness, and attempts to transform reality into something else, Denis Esakov spent more than a year painstakingly working on his series in order to create a "volumetric portrait" of each building. He invites the reader to train his or her perception and to penetrate the essence of each architectural structure shown from three points of view.

Zaha Hadid Architects: Dominion Office Building, 2015 (Photo: Denis Esakov)

Denis Esakov "lays architecture bare," showing things which we do not usually see – roofs, domes, utilities systems, and distinctive layout features – from a bird’s-eye position. His drone with built-in camera makes it possible to avoid the perspectival distortion which is often characteristic of pho- tographs taken from the ground. At the same time, we see how, when photographed from above, structures become two-dimensional. The photograph underlines this flatness and ornamentality, revealing a new urban aesthetic or showing up flaws in the urban environment. Architectural aerial photography enables us not just to see buildings from above, but also to understand how these buildings fit into the urban landscape or organize the latter.

Zaha Hadid Architects: Dominion Office Building, 2015 (Photo: Denis Esakov)

This type of photography offers a new city reception or shows the glitches in urban space. It reveals how a building integrates into the cityscape or organizes it. Although the photographs have a documentary character, they convey the impression of flying over the city. By gazing through the drone’s eye, the artist fosters a novel visual aesthetic that opens up new vistas, even for Moscow connoisseurs.