10. de març 2022

Anna Heringer (Photo: Achim Graf)

Anna Heringer has already developed projects in Bangladesh using updated traditional building methods, and she is currently implementing a school complex in Ghana. In our interview, she argues in favor of a political change of thinking towards truly sustainable action and construction in Europe.

Katinka Corts: Anna, three and a half years ago we met at the Architecture Biennale in Venice and talked about Dipdii Textiles. At the time, I was impressed that you didn’t show your own building projects at the Arsenale but instead gave priority to crowdfunding for your textile project. Today, you present your projects at exhibitions such as the current one at the Museo ICO in Madrid, and you receive international awards, while at the same time you strongly advocate the use of rammed earth in construction. How would you rate your development over the past few years?

Anna Heringer: The difference to the situation back then is that our voice carries more weight today — and it certainly has to. It’s not enough to make nice projects, you also have to speak up politically. That’s why we also do exhibitions and make more and more public appearances — it’s not about our ego. The fact that we won the Bauhaus Award and Martin Rauch was recognized for his EARTH PURE Walls helps us to get our message out: so much research and energy is being put into the development of new materials, while at the same time, clay — the “green concrete” — is available virtually everywhere as a forgotten building material.

METI School, Bangladesh (Photo: Benjamin Staehli)

With your projects in Bangladesh, you have attracted international attention for building with clay. Until today, however, clay, which also exists in Central Europe, is not considered a competitive building material. How do you see that?

Earthen building has been done for thousands of years; it simply needs more attention and the tools required for it need to be improved. Today, however, the main crux of the matter remains changing the political and economic regulatory framework. It annoys me to hear that clay has to undergo a technical development, that it has to become cheaper. No, other building methods must become more expensive! It can’t be that a building material that nature gives us for free is penalized financially in this way. Yes, it takes a lot of human labor, but it is social. At the same time, materials like concrete, steel, and aluminum are still being cheapened extremely, even though they consume so much energy.

Labor and craftsmanship remain important cost factors in projects.

Yes, but this must be addressed! Through refined techniques and tools, attempts are being made to make earthen construction more affordable, but that is not enough. At the same time, cost truth must be achieved. This is what concerns me the most. There are more and more projects that are scratching paradigms. Where it really gets down to the nitty-gritty, you realize that there must be a system change in political terms — but also in our perception and mindset and in our awareness. These are the power-sapping but also the important projects.

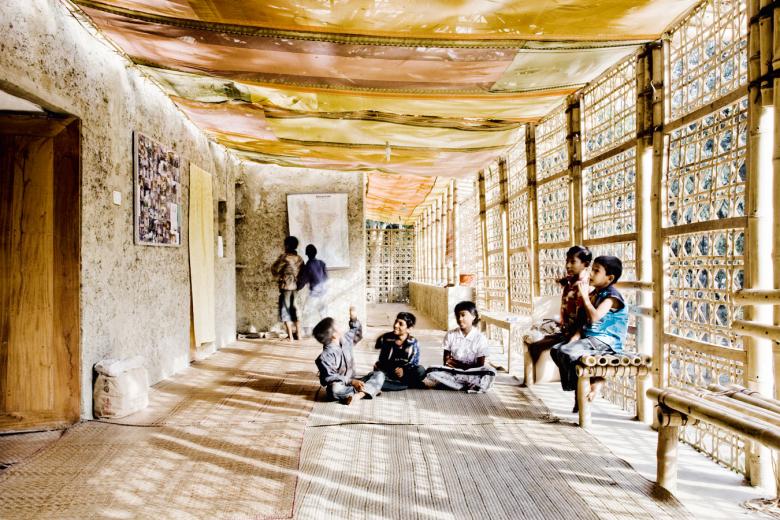

DESI Training Centre, Bangladesh (Photo: Naquib Hossain)

Wouldn’t it be necessary for clay building methods to reach dimensions that involve the implementation of large-scale projects? It always seems to me that it’s not a question of whether the projects you’re building are admirable. Rather, the transfer to Europe doesn’t seem to succeed, where the focus is much more on land use and financial return. We are definitely able to build more sustainably, but the emphasis here is different. I wonder if there is simply not enough hardship and need in Europe to think and build in a truly sustainable way.

The need actually exists, but greed is still strong. And the power is in the hands of those focused on profit. We need this power, and it is at this point that politics must take its role seriously and be on the side of the general public — and not on the side of the powerful. People always say that the market regulates everything. No, it doesn’t! That’s why we need politics to intervene and provide guidance.

Europe is currently pushing the digitalization and mechanization of buildings. You, on the other hand, are consciously using a lot of craftsmanship in your projects to make them more sustainable. I think of the mechanically operated sewing machines and the natural ventilation concepts of the METI School, for example. But the argument of "sustainability" is also used here in Europe to justify highly insulated building facades and highly sophisticated building services. What is sustainability?

Sustainability is resilience. And it is achieved by working with locally available resources. In the political crisis and the military confrontation between Russia and Ukraine, this is indeed crucial — “oh, we are energy-dependent”! We have to see what our resources are, whether in terms of energy, materials, or building materials. Obviously, that also involves saving to a certain extent.

In Bangladesh, we use solar panels on the roof. And in case of excessive use, it can sometimes happen that there is no electricity, that’s normal in Bangladesh. We in Europe always take it for granted that everything is permanently available in abundance. This leads to the rebound effect: if electricity is generated on the roof, we don’t have to save electricity any more. But we do have to save! We have to do both. Of course, we have to go high-tech, but at the same time, we have to be careful when using resources. We can’t just say that the electric car is climate-friendly, we also have to reduce individual traffic. We have to shake off this faith in technology that makes us believe that we don’t have to change and can carry on doing everything as planned. We need to arrive at a happy contentment. It is an exciting process to find out what we can dispense with.

DESI Training Centre, Bangladesh (Photo: Naquib Hossain)

Your basic inspiration for projects is absolutely social and philanthropic, always focusing equally on the needs of people, the environment, nature, and the community. What led you to develop this way of thinking? Do you have role models from your school days, from your family, from religion?

This attitude certainly comes from my family and my environment. When I was a scout, for example, I realized that I could create all the things we needed together with my group. We played music ourselves, we built furniture and tents, we thought up games. The added value of “doing it yourself” was something I experienced directly in those days. Unfortunately, we sense this kind of self-empowerment less and less in our society. We sense less and less of our own energy and power, and that’s why we constantly have to nag and block and oppose something. On the other hand, it would be much more important to reflect on our own power.

In one of your texts, I read the sentences: “In our materialistic society we are not missing materials or attraction. What we are missing is a meaning — and relationships.” For me, the Worms Altar project is a beautiful example of a return to these basic values. In St. Peter’s Cathedral, Martin Rauch and you, together with the congregation, built the new altar using rammed earth.

People stamped letters into the altar that were important to them, necklaces, personal mementos like a handful of home soil. The power you have when acting in concert as a community and creating something together became very clear here. I would like us as a society to realize that the fight for nature and our environment could be a task that unites us. When I see that new wars are being started instead, I ask myself if we don’t have more important things to do. Why are we bashing each other’s heads in and once again overlooking the fact that we actually and primarily have to work together to ensure that we preserve our planet for posterity?

That’s why it’s important to do projects where the community feels itself and is strengthened. We need many such projects. I try to make my contribution and at the same time to become louder, to be heard more. As I said before — we need to go back to what we already have available right around us and also within us and develop things from that. We don’t need the other baggage. Overflow, my God, all possessions cause enormous stress! Life is easier with light luggage.

Construction of the new altar in Worms Cathedral (Photo: Norbert Rau)

In the meantime, you are associated with UNESCO, you teach clay construction at various universities; I have read about your Laufen manifesto on human-design-culture, and your projects have received several awards. Do you have the impression that something is really changing thanks to your ever stronger presence or are many awards and committees greenwashing when using your projects? In other words, do you have the impression that you are able to make a difference today more than in the past, together with like-minded people?

For a short time now, we have also had contacts with ministries; yes, things are slowly but surely progressing. Unfortunately, politics always depends on election periods and is also slow. I think it more important that the universities become more active. The ETH now has a CAS/DAS ETH (Certificate of Advanced Studies / Diploma of Advanced Studies) in Regenerative Materials, of which earthen building is a large part. BASE Habitat in Linz has a focus on this; in Liechtenstein and Harvard, Martin Rauch and I have already headed courses on this; and in other universities such as Columbia, things are getting underway. Yes, there is always something happening, but there should be more. To be honest, I expect the universities to lead the way! Academia has to be up front, and they still take this responsibility on far too little. They have their old structures and are afraid of change — for if you teach something, you should, of course, also show this attitude in your own projects. However, it’s still too often the case, that those people are professors who are very successful in being mainstream. You have to change that.

It is certainly not very effective if your events on earthen building and traditional building methods always remain a side show and the graduates from the universities and technical colleges end up going straight into, let’s say, average offices.

Absolutely! Graduates need to get out into the field and not into offices. They have to first find their own attitude, their own path — because that’s exactly when you don’t have to pay off a loan or look after your children. I can definitely sense this desire among the younger generation, but sometimes they don’t have the necessary determination or the confidence. I try to encourage my students and tell them: have confidence, you don’t have to end up in the mainstream! Everyone is born with a certain talent and it is completely illogical not to live out these talents in life. I think that people also have to get away from the idea of a fixed income at the end of every month. That’s rarely the case for me either.

Community members stamped in personal mementos (Photo: Norbert Rau)

The unconditional basic income is repeatedly being discussed in Germany. According to its proponents, it would enable people to be creative and develop new things. It could turn Germany into a completely different location for research and knowledge.

Indeed, I also agree that the basic income is a very interesting idea that is worth testing. It’s simply important to see human labor as an energy resource. We always look at oil, wind, water and sun, but humans are also a source of energy. Oil is taxed far too little, despite its high environmental impact, but humans have to pay and give away a lot of taxes on their work. This is, for example, what makes earthen building expensive, the manual work. Actually, materials should be more expensive if they produce a lot of CO2 or are not recyclable.

Behind materials like concrete and steel, there are, of course, completely different lobbies backing them than is the case for topics like human capital.

Nevertheless, we have to hang in there and inspire people with good examples. People can definitely be enthused, and beauty and good architecture really do play a very important role in this. A good example for me is Vorarlberg, where timber construction was something completely new 30 to 35 years ago. Today it is a matter of course, and the whole industry has developed accordingly. It took a generation, but it also started with a few people who were declared cranks. Every movement started with a few people, and systems can change.

Are your projects like the METI School and the DESI Center being copied in neighboring communities; in other words, do you notice that you can act as a kind of role model with your sustainable, local construction methods?

Well, that takes a lot of patience. First there was the colonial period, then missionary work, and finally so-called development aid. And building methods were always different. When you drive around Bangladesh, you see an advertisement for cement, aluminum, or air conditioners every hundred meters. Obviously, a handful of projects is only a start. Nevertheless, architects in Bangladesh now also perceive clay as a sustainable and modern building material.

A project by Studio Anna Heringer and Lehm Ton Erde – Martin Rauch (Photo: Norbert Rau)

You are currently building a school campus in Tatale, in the northeast of Ghana. You are women from Europe who go to a multi-confessional, patriarchal region and advocate for new (old) building methods. Is that working out well?

Well, in Ghana, it is actually a struggle. The Catholic Church — just as all governmental and non-governmental organizations — has been building differently in Ghana for decades, mainly using concrete. Now, all of a sudden, a woman from Europe comes along and tells them to do it differently. There is definitely a difference between what the Austrian Salesians think and what people think who have been in Ghana for a long time. You have to approach things slowly, build up trust, and prove yourself. I realize that good architecture is helping the process. As is patience.

In Bangladesh, we are currently facing the problem that the government is distributing corrugated iron huts for free as part of its development program. Now people tear down their mud houses to put up the corrugated sheets. As a result, the most beautiful village looks like a slum! Exactly where I thought we were on a good way, the government launches such a questionable program. Of course, the people in the village know that they can build a mud hut themselves, but the corrugated iron is worth such-and-such Bangladeshi Taka. That’s why they don’t refuse this gift; but they don’t consider the fact that it is extremely hot inside the hut in the summer, freezing cold in the winter, and that it looks shabby after ten years. But maybe they have to experience this once again, and in the meantime, we continue to work and present alternatives. Sometimes it is quite tedious.

Nevertheless, we are not giving up. I am and remain an idealist, and I am convinced that we have the power for change, for good and peaceful development in our hands and thoughts.

Dear Anna, thank you very much for your time. Please keep up the good work, all the best for your projects in Ghana and wherever else you go!