Exhibition Review: HOT TO COLD

John Hill

2. Februar 2015

All photos by John Hill/World-Architects, unless noted otherwise

Bjarke Ingels Group has followed up last year's successful BIG Maze at the National Building Museum by ringing the building's atrium with 60 of their projects to take visitors on "an odyssey of architectural adaptation" from hot to cold climates.

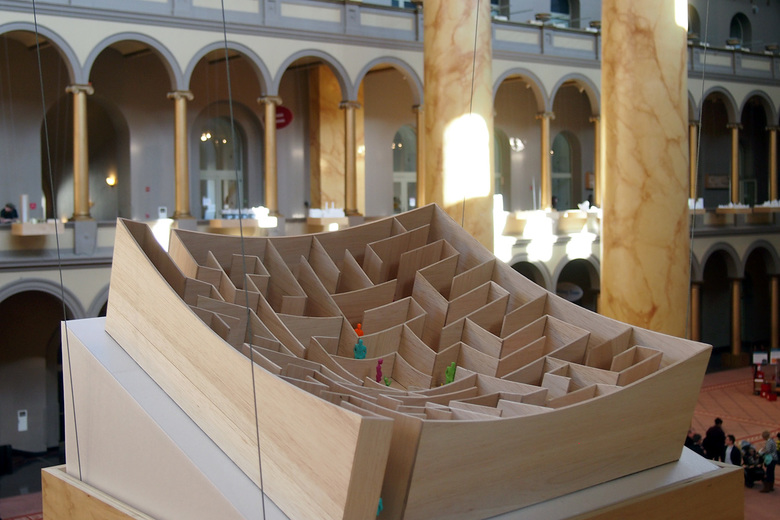

Just as the BIG Maze reconsidered what a labyrinth could be, by taking a primarily two-dimensional construction and imparting some three-dimensionality through successively shorter walls toward the maze's center, HOT TO COLD questions what the form of an architectural exhibition should be, by integrating it into the NBM's huge atrium rather than squirreling it away in one of the side galleries. This ambitious approach is in line with BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group's ambitious global architecture, which purports to be climatically responsive and an extension of Bernard Rudofsky's "architecture without architects," what founder Bjarke Ingels calls "engineering without engines."

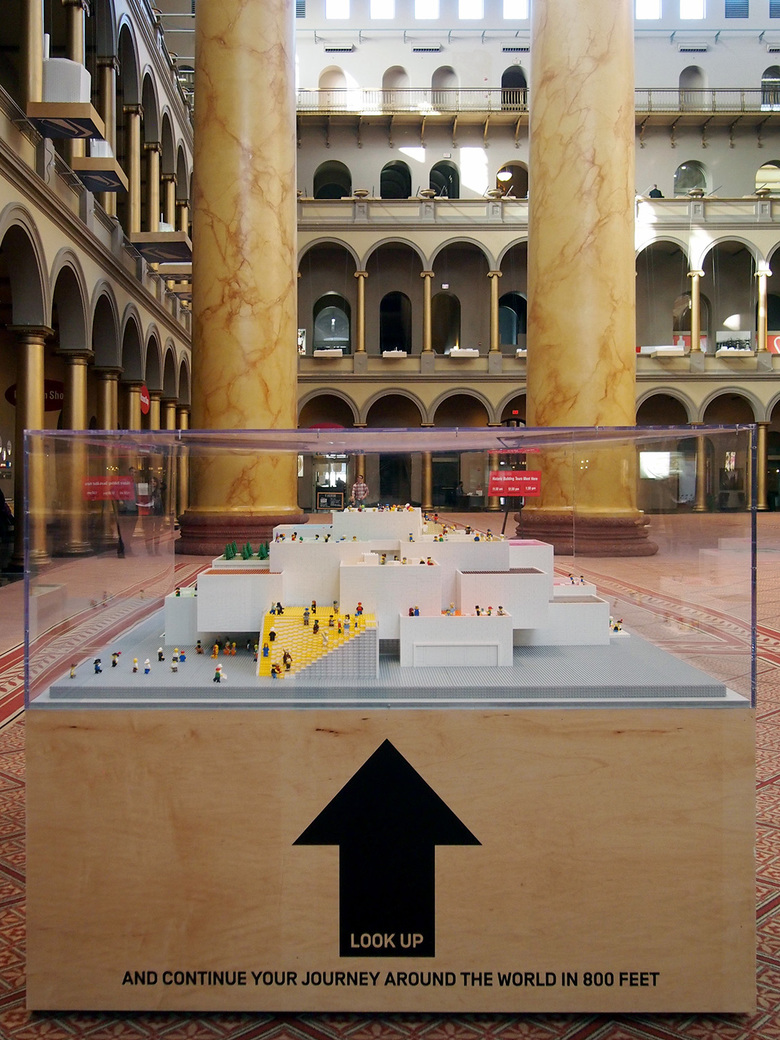

LEGO House model on the atrium's ground floor

Yet the scale of the BIG's exhibition is hardly felt upon entering the museum. A few steps past the south entrance sits a LEGO model of the LEGO House now under construction in Denmark; it, and virtual reality goggles that immerse visitors in last year's BIG Maze, are the only exhibition pieces on the museum's ground floor. The base of the large LEGO model instructs visitors to "look up and continue your journey around the world in 800 feet," the diameter of the second-floor arcade where the projects are displayed.

The underside of four of the models in the exhibition's COLD section

A look up reveals icons – familiar to those who have ever visited big.dk – that cover the underside of the model bases suspended from the third-floor arcade. The form on each icon signals the project, while the color is coded to the project's climate, from red in the Middle East to blue in BIG's native Denmark. Many of these models are quite big, but they appear as small as pixels inside the "screen" of the four-story atrium and its eight massive Corinthian columns.

The globe marks the beginning of the exhibition and the arrow indicates the direction of the odyssey of architectural adaptation.

A stairway next to the main entrance, just behind the LEGO House model, is the main access to the exhibition one floor up. Atop the stair is a globe whose colors reference average temperatures, red around the equator and purple and blue toward the poles. Logically the globe marks the beginning of the exhibition – the first of 76 arcade bays featuring models and displays on the 60 projects – but it also serves a suitable symbol for BIG's ambitions; after all, how many architecture firms could present so many projects created within the span of only five years, projects reaching just about every corner of the globe? Ingels' previous employer, OMA, may come to mind, but very few other firms would fit the bill, or have the charisma and audacity to pull it off.

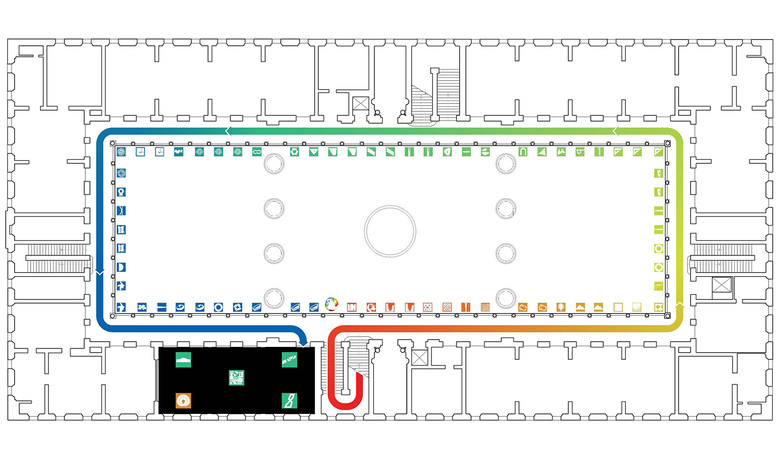

Exhibition layout, showing the counterclockwise path from HOT TO COLD and the darkened side gallery with videos at the end of the 800-foot lap. Image courtesy of BIG/NBM

One bay to the right of the globe is, appropriately enough, the HOT TO COLD exhibition and the BIG Maze. Just as the globe takes on a symbolism about the firm's global ambitions, these two projects – existing outside of the HOT TO COLD spectrum – signal BIG's ambitions in Washington, DC. As Ingels told some press assembled for a preview of the exhibition on a snowy January day a couple weeks ago, it was three years ago when he first visited the nation's capital, coming down from BIG's now 130-strong New York City office. He made that first trip when they were "gunning for the Smithsonian South Mall Campus master plan," which they were awarded and unveiled last year. The 60-project exhibition seems to tell visitors that the Smithsonian is in capable hands. Or as Washington Post architecture critic Philip Kennicott put it in his review of the show, "No matter what one may think of the $2 billion initial plan the Smithsonian unveiled in November, the clarity and ingenuity of BIG’s portfolio gives one confidence in the firm’s ability to adapt, rethink and improve its Smithsonian designs."

Model of the BIG Maze

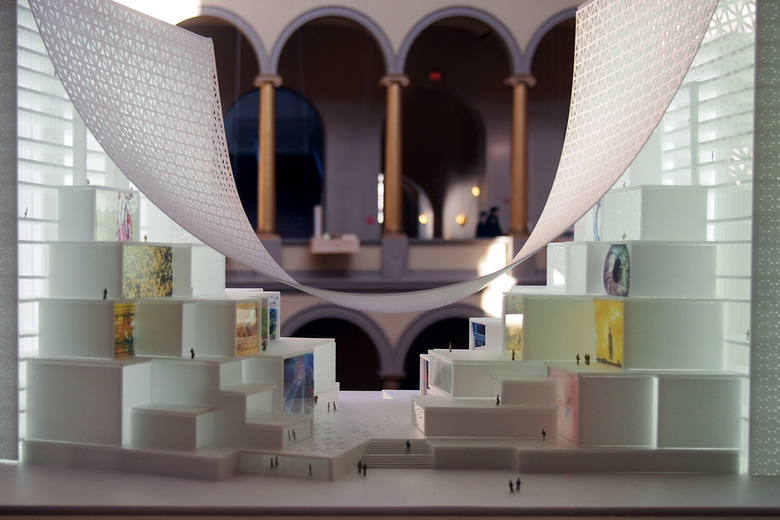

"Magic Carpet" media headquarters for somewhere in the Middle East

The "architectural odyssey" proper starts to the right of the two NBM projects with a media headquarters designed for somewhere in the Middle East. BIG's "Magic Carpet" moniker might sound like a caricature at first blush, but it is fitting, since the most striking gesture is a tensile membrane that is draped from one tower slab to an identical one set at a slight angle. This gesture, one of the first images encountered by museum visitors, is a strong illustration of how Ingels and his team find inspiration in the climate-responsive vernacular of a place. Stacked boxes sit below the "carpet" and are shaded be the patterned openings of the roof tiles to create usable outdoor spaces for the hot desert climate.

Southeast corner of the exhibition with a full-scale mockup of the facade for the Hanwa Research Center

Ask anybody from BIG and, like any architect, they are sure to say that every project is important – built or unbuilt, big or small, hot or cold, they all receive the proper attention and yield important design insights. Nevertheless, there are certain exclamation points that occur along the 800-foot path of HOT TO COLD. A few occur at the corners, and the first one encountered is home to a full-scale mockup of a louver system for the facade of the Hanwa Research Center in Seoul, Korea. It is the only full-scale piece in a show with models ranging from study models a few inches tall to large-scale finished models taller than a person. First seen as an image in the distance, the mockup becomes a screen to look through after turning the corner.

A glance at some of the HOT projects, including the lollipop-like BIG PIN planned for Phoenix, Arizona

Study models for Rose Rock International Financial Center in Tianjin, China

Another exclamation point, if you will, happens at the midway point of the short, east end of the atrium, where numerous models for the Rockefeller City-inspired Rose Rock Financial Center for Tianjin are displayed. The models – one of them at least 10 feet high – seem to play with the eight large columns of the NBM atrium, as seen in the photo above. This visual effect would not work if the project fell somewhere else within the HOT TO COLD spectrum, so I contend that the projects are located for impact as much as they are the result of scientific data about climate. How else to explain that a number of Copenhagen projects fall at about the midway point of the exhibition (in the green colors), but the city's Amager Resource Center is the last, and therefore coldest, project? As we'll see it's about making a statement.

Large model for W57, New York, sitting in the northeast corner of the atrium

The northeast corner of the exhibition is where W57, a tower under construction on Manhattan's West Side, is located. This is the project that, one could argue, brought Bjarke Ingels to America, leading him to open his New York office and rapidly expand the firm's reach. As I learned firsthand with a visit to BIG's NYC office in 2013, projects followed in Vancouver, Arizona, Miami, and plenty of other places beyond BIG's native Denmark. As W57 nears completion, and other projects documented in HOT TO COLD take the leap from foam cutter to reality, this reach will surely continue.

Study models for LEGO House

Bjarke Ingels giving the press a tour of the exhibition a couple days before opening day

Having written "foam cutter" instead of "drawing board," I should probably say a few words about BIG's models. A visit to BIG's website yields project explanations built around step-by-step diagrams that convince us that the somewhat odd design we are looking at is the outcome of logical responses to certain factors, be it sun, wind, temperature, culture, or economics. Yet HOT TO COLD plays down the diagrams in favor of the models – most of them in foam – that hang in the atrium and invite us to subtly lean over the displays of renderings to get a closer look. The models, which are lost like pixels when seen from below, are the strongest parts of the exhibition upstairs. Just out of reach, they are nevertheless the most understandable things on display, giving visitors three dimensions of appreciation.

Looking down length of arcade with Bunker Museum project in the foreground

Steel model of Watch Flower viewing platform designed for Aarhus, Denmark

With so much foam, one of the most striking models is the 140-pound steel model for the "Watch Flower" viewing platform in Aarhus, Denmark. The "engineers without engines" mantra applies directly to this design, which eschews a budget-gobbling elevator in favor of a ribbon-like, 500-foot-long ramp; this happens to be roughly the distance visitors have traversed to get from the globe to this northwest corner of HOT TO COLD. BIG designed the ramped platform as a monolithic steel structure of welded steel, so they had a model built of the same as a means of testing the concept.

Model of Faroe Islands Education Center in the southwest corner with globe in the distance

Arrow pointing to the last COLD leg of the exhibition

Having followed the large arrows on the floor for 800 feet, the last project museumgoers see in the second-floor arcade is the Amager Resource Center, now under construction in Copenhagen. Coming last yet, as mentioned, out of place within the HOT TO COLD spectrum, the project makes a statement about BIG's design thinking and future. For one, it is being built and will therefore literally make a mark on the world. But more importantly, the almost surreal positioning of a ski slope above a waste treatment facility says a lot about an architect considered one of the most innovative today. The term innovation is devoid of meaning through overuse these days, but in BIG's hands innovation is the creation of something new from things that has existed all along. It could be combining two typologies – a courtyard building and a skyscraper – to create a "courtscraper" for Manhattan's West Side, for example, or, in the case of the Amager Resource Center, of adding a recreational benefit to an industrial facility. It's about having both/and not either/or, and therefore it's not surprising that Ingels originally wanted to call the NBM exhibition and companion book "BIGAMY."

The last section of the HOT TO COLD with model of Amager Resource Center in the foreground

Side gallery with films, more models and seats for watching the films

Even after the fairly exhausting 800-foot lap around the NBM atrium, HOT TO COLD still has more to offer. In a side gallery next to the stair we first ascended are films on some of BIG's completed projects. This makes sense given that the one element missing from the 60 projects in the atrium is, well, life. The projects are lively, to be sure, but they have yet to be occupied, modified, defaced – lived in. This darkended gallery examines through the lens of filmmakers what has transpired in buildings like the 8 House and landscapes like Superkilen, serving as a flipside to the design process documented in the atrium. The films illustrate that Ingels and his team care about how their built projects have evolved, but the 60 projects taking over the atrium tell us that BIG's gaze is aimed squarely on the future.

Large illuminated model of 8 House with film by Beka & Partners on the wall

HOT TO COLD: an odyssey of architectural adaptation is on display at the National Building Museum until 30 August 2015.

John Hill