From Switzerland to Wisconsin: The Curious Case of New Glarus

John Hill

4. November 2022

Photo © Brian Griffin

The award-winning book Swissness Applied focuses its attention on New Glarus, the tiny Wisconsin town whose downtown buildings draw tourists through facades that exude Swissness. World-Architects editor John Hill delved into the book by Nicole McIntosh and Jonathan Louie of Architecture Office to learn about the town and understand how the pair of architects are "learning from New Glarus."

Most building codes exist to protect the health and safety of people occupying buildings erected in a jurisdiction. While the particulars of building codes vary from place to place, for the most part they prioritize how buildings function and perform rather than how they look. Put simply, the fact a building stands up is more important than its outward appearance. Form-based building codes — aka architectural codes — do exist, though, the most famous being for the Town of Seaside on Florida’s panhandle. First written in 1980 and revised numerous times since, the code dictates many aspects of the buildings in the small vacation town: roof pitches, exterior cladding, fences, doors and windows, and advertising signage (or lack thereof), among other things. Though rooted in traditional designs, the code stops short of mandating a particular style, resulting in buildings that veer from the vernacular and the classical to the (mildly) modern; overall it is an eclectic townscape that does not follow one particular style.

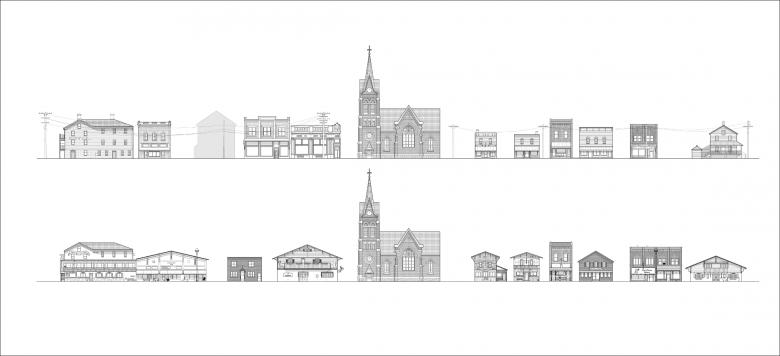

About 1,000 miles north of Seaside sits New Glarus, a tiny village in Green County, Wisconsin, with a population of just 2,266 people, per the 2020 census. New Glarus has its own form-based code, but it is considerably different from Seaside’s. The code can be gleaned from the name of the village, which comes from Glarus, the city and canton in the middle of Switzerland. New Glarus in 1901, when it was officially incorporated, did not resemble what it does today: a Swiss town transplanted to the American Midwest. A chapter in the town’s administrative code, first adopted in 1999 and updated since, has defined a “Swiss Architectural Theme” for its eight-block downtown and a one-mile stretch of highway linking the town to Madison, the capital of Wisconsin, to the north, and Illinois to the south. Even though New Glarus did not initially resemble Glarus, why did it eventually adopt a legally prescribed stance toward architectural style? And what can architects learn from such an apparent anomaly? These and other questions are the subject of Swissness Applied: Learning from New Glarus by Nicole McIntosh and Jonathan Louie.

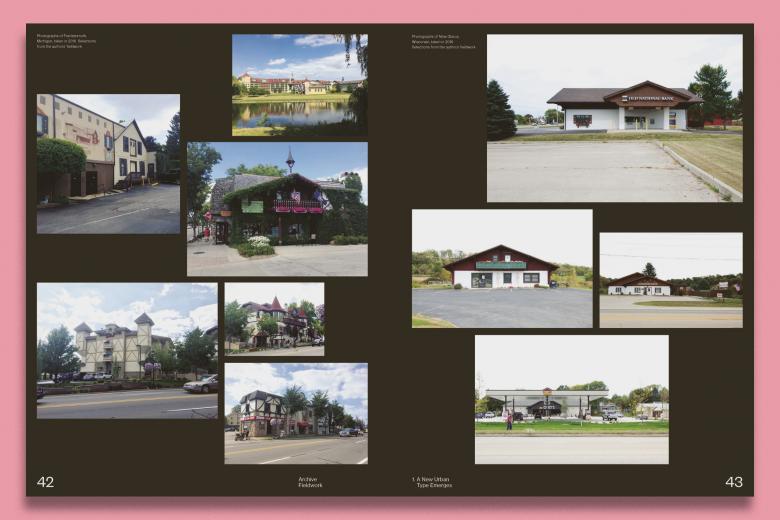

Spread from Swissness Applied with photographs of New Glarus, Wisconsin. (Image courtesy of Architectural Office/Park Books)

The Swissification of New GlarusGlarus residents experiencing economic hardship in the mid-1800s emigrated to the United States, founding New Glarus in 1845 on land that three years later would become part of Wisconsin. New Glarus was one of a few such European immigrant towns created in the 1800s, among which are also Frankenmuth, or “Michigan’s Little Bavaria,” and Solvang, “California’s Little Denmark,” as explored by the authors early in the book devoted to New Glarus. Although New Glarus was not anomalous as an American town of European transplants, the original settlers shied away from transplanting the architecture of their homeland. It was not until the mid-1930s that the Swiss chalet made an appearance in New Glarus, with two buildings designed by Jacob Rieder, an architect who emigrated from Switzerland. He designed Bigler’s Swiss Tavern (now Ott Haus) for Fred Bigler, who himself came from Switzerland and carried out the brickwork at the base of the two-story building; the upper story, framed and clad in wood, turned the building effectively into a chalet topping a commercial base. Two years later, in 1937, Rieder designed the Chalet of the Golden Fleece, which the authors call “the first authentic Swiss chalet” in the town and is now a museum listed on state and national historic registers.

Just as New Glarus was born from economic hardship, the full-blown “Swissification” of the town followed the 1962 closure of the Pet Milk Condensing Plant (formerly the Helvetia Milk Condensing Company), which employed one-third of the town’s residents. With the two Rieder buildings from the 1930s and one from the following decade giving the Wisconsin town a Swiss flavor that it was already celebrating with annual festivals, the town latched onto its Swiss image and reoriented itself toward tourism. This shift happened informally and haphazardly at first, with buildings in the 1960s and 70s cobbling together architectural elements that would appear on Swiss chalets, an “ad hoc technique [that] yielded various interpretations of how to Swissify buildings yet lacked an overall planning strategy and visual coherence,” in the authors’ words. Some coherence came via Madison architect Stuart W. Gallaher, who was trained in Swiss building and had amassed books on the subject as well as albums with photographs of traditional buildings in Switzerland, Austria, and Germany. Gallaher’s research and collaborations on buildings in New Glarus segued nicely into the official Swiss Code that was implemented in 1999 and which mandates the Swiss style for the two parts of the town, mentioned above, that are deemed important for its stability as a regional tourist attraction.

Elevations of 1st Street, New Glarus, in 1900 and 2020. (Drawing courtesy of Architectural Office)

Learning from New GlarusThe book’s subtitle clearly references Learning from Las Vegas, the seminal 1972 book by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour that led to dozens of “learning from” studies in architecture and urbanism, the present book included. Las Vegas as an urban condition relevant to architects makes some degree of sense, but why New Glarus? And is another book about the town warranted? New Glarus has been the subject of numerous books, most of them looking at the town's origins and its evolution since, so another book recounting its history was not necessary. But Swissness Applied is much more than history. In the hands of Nicole McIntosh, who studied at ETH Zurich before heading to the United States, and Jonathan Louie, her partner in Architecture Office and fellow (former) assistant professor at Texas A&M University, the book captures their interest in “the way images construct our built environment and, more specifically, how the heritage of place manifests elsewhere,” as they state in the introduction.

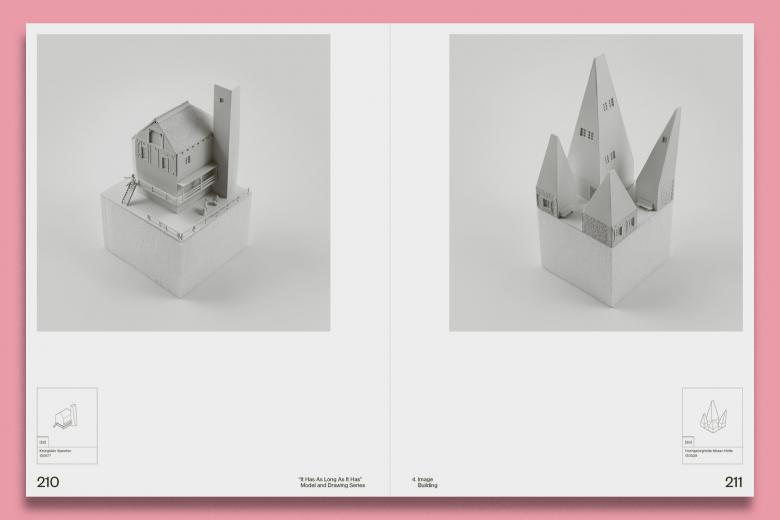

New Glarus is therefore a fitting site for studying the role of images in constructing the built environment, and appropriately Swissness Applied is loaded with images: contemporary photographs of “Wisconsin’s Little Switzerland,” historical photographs of Swiss chalets, line drawings of buildings in New Glarus, paper models — or “John What Henry” (“Hans was Heiri”) models — of buildings in town, and basswood corner models of buildings in the Downtown Commercial District. The models came out of a traveling exhibition also called Swissness Applied, curated by McIntosh and displayed at architecture schools and museums in Milwaukee, Glarus, New Haven, and Denver between 2019 and 2021. And lest we forget that Learning from Las Vegas featured Venturi Scott Brown design projects alongside the research carried out by Yale students, near the end of Swissness Applied is a chapter with fictional models and drawings where “the authors remix building elements of Swiss architecture using Swiss-themed” model kits that interpret the criteria from New Glarus’s form-based building code. One need only look to Steven Holl’s modern insertion into the traditional townscape of Seaside to find relevance for Architecture Office’s designs that depart from the Swiss chalet style but still, they believe, “exude Swissness.”

Swissness Applied at Sarup Gallery, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Architecture & Planning (April 12 – May 3, 2019). (Photo © Brian Griffin)

Award-Winning BookSwissness Applied was published by Park Books one year ago and reviewed by Susanna Koeberle on the Swiss-Architects platform in April of this year. The book is making an appearance on World-Architects now after it was named one of the ten winners of the DAM Architectural Book Award 2022 last month. The jury wrote that the exhibition catalog was done “in an incredibly beautiful, clear, simple, and delicate manner.” The jury commendation, written by Brigida Gonález and Anna Kraus, continues, in part:

“The typologies are documented in a strict, formally defined way. In the best manner of Hilla and Bernd Becher’s photographs, the houses are all uniformly captured under a cloudy sky. All the models are built from the same material and shot in studio in a uniform photographic style. The architectural drawings could hardly be more reduced. All representations follow the same pattern. There is nothing to distract the eye, no unimportant details – the reader is only meant to be able to distinguish the various types. Only in this way can the idea succeed, and we the viewers can gain an ‘image’ of it.”

It is hard not to agree with the praise levied on the book, which also features contributions (by Marc Angélil and Cary Siress, Philip Ursprung, Kurt W. Forster, Whitney Moon, Jesús Vassallo, Courtney Coffman, and Patrick Lambertz) that greatly expand the issues covered by the authors. The drawings, photographs, and models strongly convey the character of New Glarus, an unexpected testbed for architectural explorations by McIntosh and Louie. Normally, for this reviewer, the success of a book about a particular place is gauged by its ability to instill a desire to go and see the place in person. This book, while it does not do that, doesn’t have to: its emphasis on the role of images in constructing a place means that seeing images of New Glarus is sufficient. Those images in their multifarious nature (old and new, Switzerland and America, drawings and models, buildings both real and imagined) provide plenty to learn from, though they also spark a lot of joy — not an easy feat in an architecture book.

Spread from Swissness Applied with "It Has As Long As It Has" model and drawing series. (Image courtesy of Architectural Office/Park Books)

Swissness Applied: Learning from New Glarus

Nicole McIntosh und Jonathan Louie

23 x 30 cm (9 x 11 3/4")

272 Pages

280 Illustrations

Paperback w/Swiss brochure binding

ISBN 9783038602446

Park Books

Purchase this book