Spolia in the Wall

Ulf Meyer

6. junio 2019

All photos courtesy of Erimtan Museum

The Erimtan Museum in Ankara, Turkey, designed by Ayşen Savaş with Can Aker and Onur Yüncü, is, in the words of Ulf Meyer, a well-kept secret on the same level with some of Carlo Scarpa's finest works.

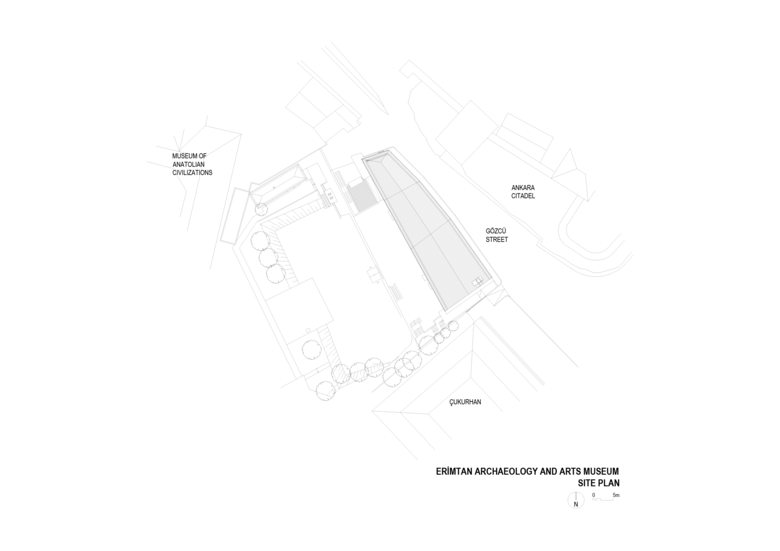

The Turkish capital, Ankara, is an interesting city. In less than a hundred years it has grown from a tiny Anatolian town to a metropolis of well over five million inhabitants. Tourists traditionally ignore the city entirely because they think the sprawling capital offers few attractions aside from the Atatürk Memorial. Just as the city does not get much attention, neither does an architectural jewel that can be found right next to the fortification walls of the Citadel of Ankara. The Erimtan is a carefully designed and crafted museum whose attention to detail and innovation in display techniques is astounding and puts it on a level with some of Carlo Scarpa’s finest works.

The museum is the work of Ayşen Savaş, who was joined by Can Aker and Onur Yüncü on the technical aspects of the building; Savaş also designed the exhibition. They transformed three historic houses from the 18th century into a marvelous museum. A path connects it to two nearby museums, the famous Museum of Anatolian Civilizations and Koç-Museum, as well as nice caravanserais and the citadel square. The three attached houses were completely dismantled and rebuilt, because their state of ruin was too far to fix. However, the new building is not a replica, it is a careful modern interpretation that follows its predecessors in volume and expression and sports the same intricacies of masonry techniques for its heavy grey stone walls. The rocks were numbered before demolition and replaced in their original locations. The mortar joints, the depth of the window frames, the order of roof tiles, and the thickness of the threshold stones were inspirations for the new architecture. The Ankara stone has been complemented with concrete, terracotta, copper, cast iron, and wood, striking a delicate balance between historical and contemporary details.

Erimtan Archaeology and Arts Museum was founded in 2015 by the Association of Collectors of Cultural Assets and named after its founder, Yüksel Erimtan. The civil engineer and an archaeology enthusiast, who began acquiring ancient jewelry in the 1960s while working on construction projects in southern Turkey and later widened his collection with coins, seal stones, glass and ceramic objects, contributed his private collection to the museum. The Association rents the buildings from the city and spent 10 million Turkish liras (only 1.5 million in today's Euros) to renovate them in 2015. The museum consists of nearly two thousand artifacts, almost all of Anatolian origin. Although the collection covers a period of time extending from 3000 BC to Byzantine times, most artifacts are actually Roman. Glass, gems and coins are the outstanding groups among the collection.

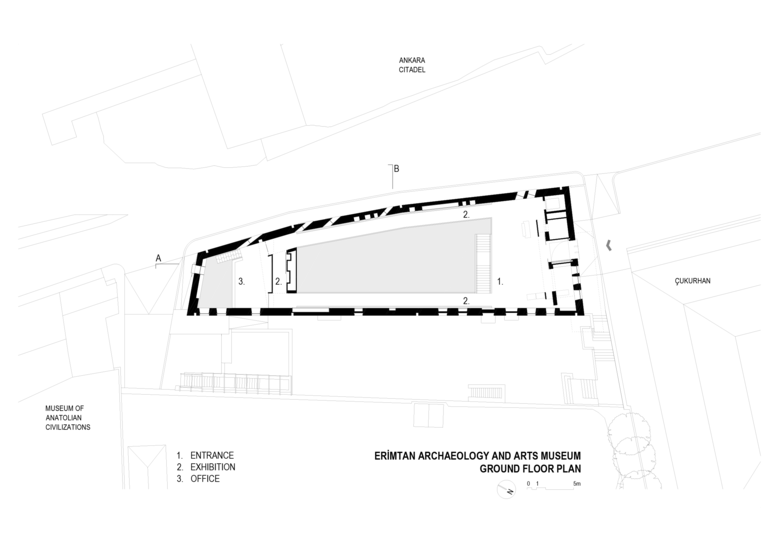

The entrance to the museum is emphasized by a beautifully detailed copper door and a wall of text relief. The low façades enhance the nearby citadel fortifications and form a continuous stone wall. Windows are interpreted as viewpoints and have arches formed out of cut stones and keystones. These reconstructed details were "treated as documents," according to the architects and resemble them in "scale, space, detail and material" — but with a twist. The openings mirror spolia from the Citadel fortifications that act as displays. The Citadel walls incorporate sculptures, capitals, stone ornaments, and pieces from antique columns. The spolia determine the depth of the walls and windows.

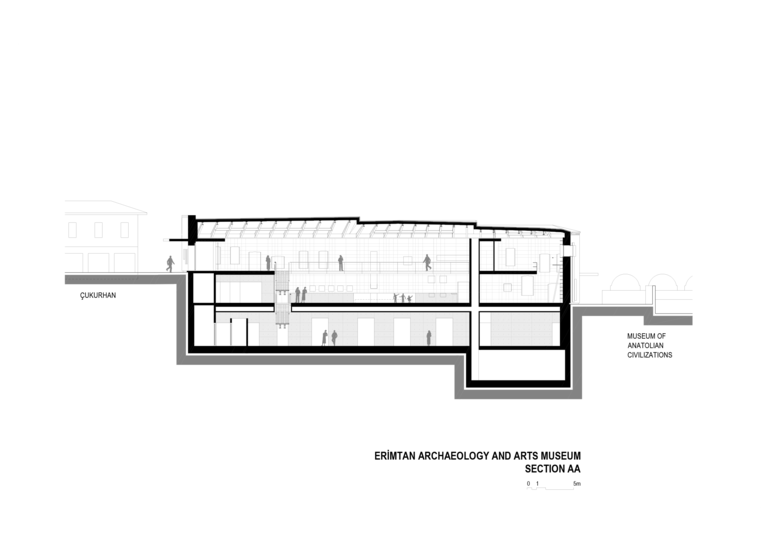

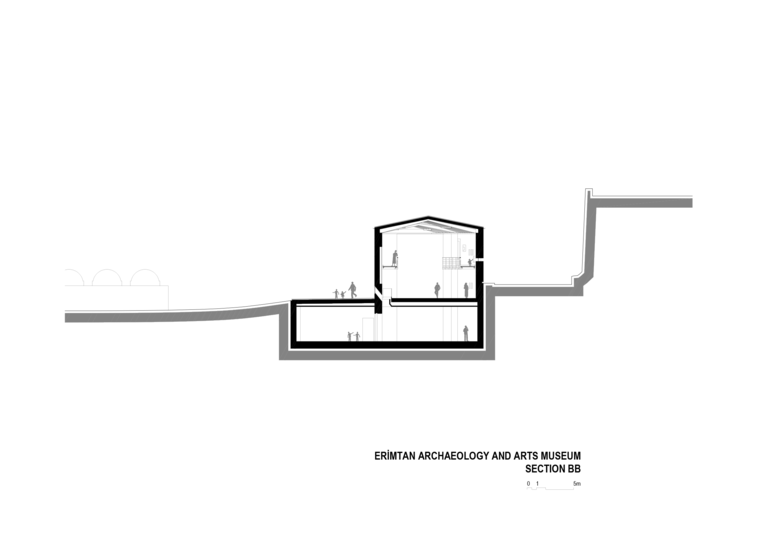

Contemporary l-beams were placed at the borderline where the houses meet the ground. Thus, the heavy load of the masonry walls is alleviated with a strong cut from the ground, and raised on a line, in order to reframe the houses and to be perceived as a single mass. A thin copper line on the exterior highlights the borders of the three houses, while the vertical water pipes together with the horizontal rooflines keep the houses together.

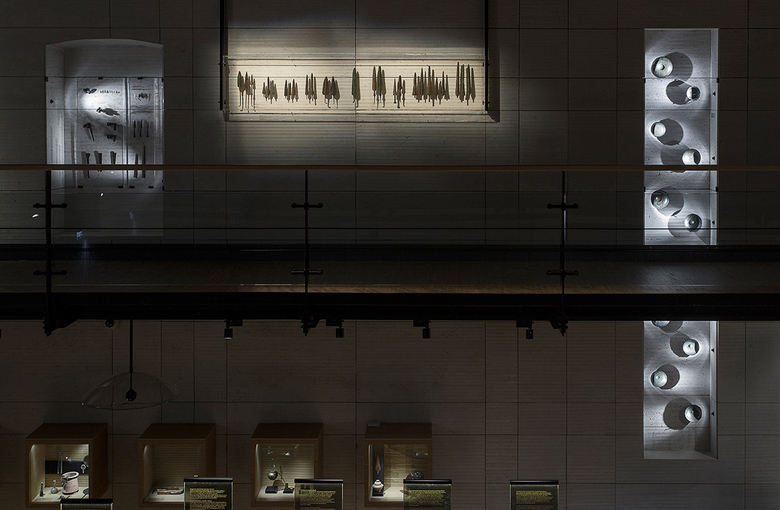

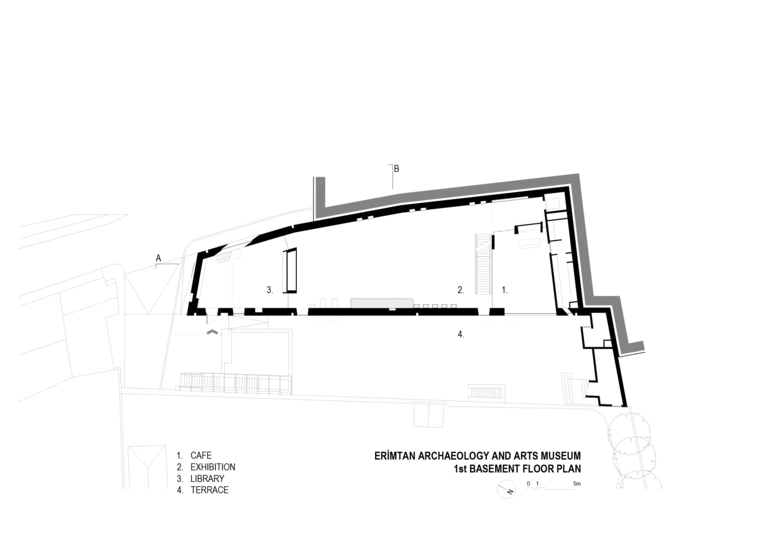

A vestibule on the mezzanine floor provides views of the custom-made display cases along two catwalks at the long western and eastern sides of the hall. Beautifully crafted stairs connect the permanent exhibition area below to this temporary exhibition floor. Carefully designed electric light illuminates the objects in front of a dark background. Counterintuitively, there is more light in the underground spaces. The concrete roof rests on steel beams and the thick walls are perforated only by display cases. While the black l-beams divide the museum into three units, the interior is still perceived as one space. The walls are slightly angled, creating a sublime sense of infinity learned from Baroque architecture to create an optical illusion diminishing towards the vanishing point.

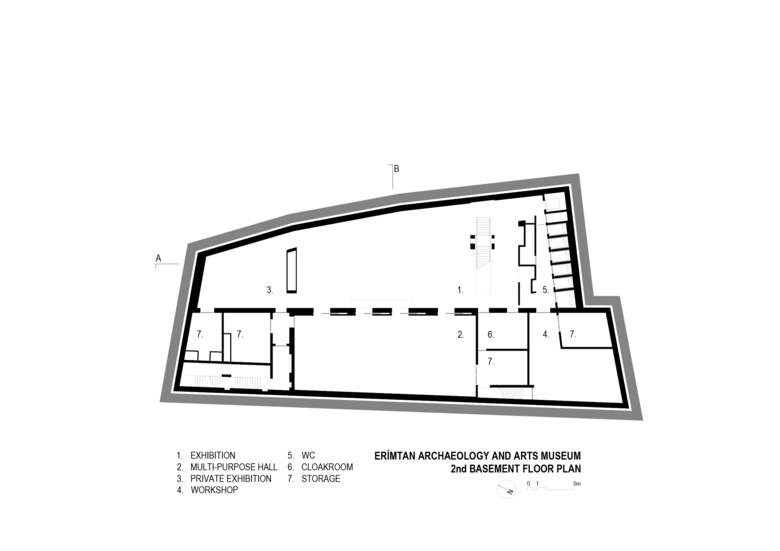

The museum café has a large terrace with prominent views of the Turkish capital city. Below the terrace sits a multi-purpose hall and an adjacent piano room for recitals and chamber music. The library, itself a beautiful spatial creation with a large built-in shelf, has double height along the north façade. The library and the workshops have their own entrances. The south façade is expanded to accommodate gift shop, information counter, lockers and elevator, with kitchen, storage and equipment room below.

The renaissance of the three houses as a private museum under the guidance of talented architects is an interesting case of architecture that cleverly blurs the lines between preservation, restoration, conservation, and reconstruction. The concept of using spolia has proven to be powerful, so the Erimtan museum adds a true bijou to an otherwise overlooked metropolis.