Dense, Big, Stirring – 'Architecture Matters'

Elias Baumgarten

21. mai 2019

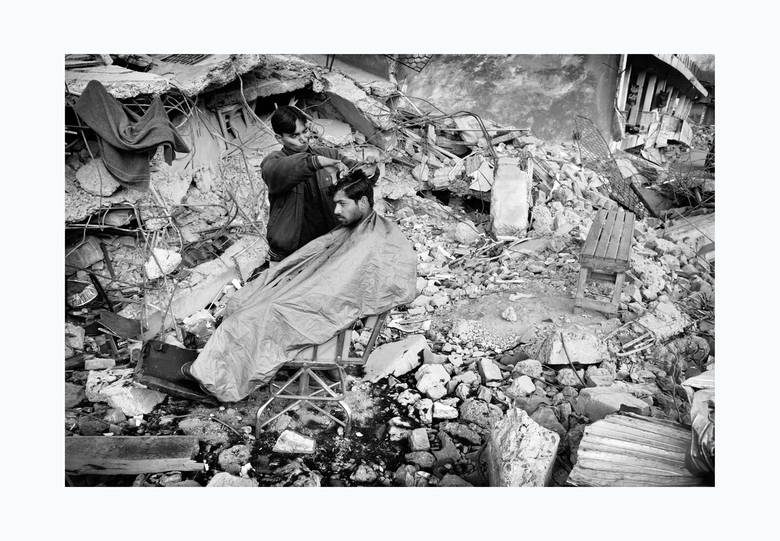

At “Architecture Matters,” Jan Grarup showed selected images from his work as a war photographer. This picture was taken in 2005 in Balakot in the Kashmir region of Pakistan. (Photo © Jan Grarup)

Two days, 17 speakers, 5 events: the “Architecture Matters” conference took place in Munich on April 11 and 12, 2019. The highlight was Friday’s dense program of lectures and discussions spread across the afternoon and evening. The conference was organized for the fourth time by the curator and author Nadin Heinich’s firm, plan A – Office for Architectural Communication and Urban Culture. Among the many lectures, two especially stood out: the one by the founder of the Zurich startup Archilyse, Matthias Standfest, and the one by photographer Jan Grarup from Denmark.

- The theme of the conference was clearly expressed in its title: "Great Ideas, Large-Scale Projects and Disaster." The line-up of speakers and the issues they addressed largely continued the debates from the previous year. There was, for example, a renewed call for solutions to the crisis in the German housing market. New this year was talk about the digitization of the building process.

- This review focuses on the lectures by Matthias Standfest (given at the kick-off event) and Jan Grarup.

On the Thursday, “Architecture Matters” got off to a quick start with an evening event on the digitization of the building process. The next day, a workshop and two networking events for young architects, project developers, and journalists took place even before the actual conference – which continued into the evening – was held.

Couple in Haiti after the earthquake’s destruction (Photo © Jan Grarup)

Particularly at the latter event, the debates of the previous year were continued. The topics of discussion were sustainability, densification, and solutions for the strained situation on the German housing market. Quite a few speakers were once again on the podium, such as Munich’s current urban development commissioner, Elisabeth Merk, and her predecessor, Christiane Thalgott. The talk did not go beyond fairly general finger-pointing between the politicians and the project developers. The developers were accused of lacking architectural and social ambitions. No proposed solutions to the housing crisis in Germany were presented. However, exciting large-scale projects of the kind promised by the event’s title were shown by Christoph Ingenhoven, who spoke about Stuttgart 21 and the colossal residential development “Green Heart | Marina One” in Singapore, and also by Jan Knikker, who stood in for Winy Maas, who was absent due to illness. Knikker presented MVRDV’s largest buildings, including Rotterdam’s central market hall.

But two other lectures were particularly memorable: Matthias Standfest, a trained architect and young entrepreneur based in Zurich, spoke about his software, which can be used to assess “architectural quality.” And Jan Grarup from Denmark gave an exceedingly impressive presentation about his experiences as a war photographer.

Discussing the situation on the German housing market: Tobias Sauerbier (SIGNA), Regula Lüscher (Chief Planning Director, Berlin), Christiane Thalgott (former Urban Planning Commissioner, Munich), Elisabeth Merk (Urban Planning Commissioner, Munich), Christoph Ingenhoven (Ingenhoven Architects), and Franz-Josef Höing (Chief Planning Director, Hamburg). (Photo: Tanja Kernweiss)

Matthias Standfest giving his lecture (Photo: Tanja Kernweiss)

Algorithms Assess “Architectural Quality”The first sensation came from Matthias Standfest at the kick-off event on Thursday evening. Standfest is the founder of the successful Zurich startup Archilyse. He had been invited to introduce his company and its services. He and his team of nine have developed algorithms intended to evaluate “architectural quality.” Clients pay for licenses to use them. Fed with addresses and floor plans, the software supplies data on views, location, compliance with norms and standards, and the efficiency and functionality of layouts, along with thermal, acoustic, and structural analyses. In this way, the (economic) performance of a building can be evaluated. In the wink of an eye, this information is then compiled as a PDF with pretty graphics that are easy for anyone to understand. Standfest explained that his assessments are currently being used primarily by developers and investors, who gain insights on maximum rental prices, for example, that enable them to optimize their business dealings. In this way, many real-estate owners have realized that the rents they charge are too low. Standfest wants his algorithms to be understood as tools for optimizing the entire value chain. He revealed that the software can and should also be employed to evaluate designs for new buildings and competition entries – and that behind the scenes this has already become a real possibility. His clients and prospects already include the most important players in the Swiss real estate industry. Migros and Swiss Life, for instance, are already using Archilyse software to optimize their real estate businesses.

Thought through to the end, this poses a big potential danger for tenants and architects – and Standfest sees that too. With little emotion, he noted that architectural practitioners are in great danger of becoming obsolete as a result of digitization. Almost spitefully, he said that thanks to his services, in the future they could concentrate entirely on design and would no longer have to worry about devising ideal floor plans or adhering to norms and standards. Moreover, the interests of tenants, who may soon have to dig even deeper into their pockets thanks to the deployment of his software, also seem to be of little interest to him.

Paul Indinger (Building Radar), Patrick Christ (Capmo), Tobias Nolte (Certain Measures), and Matthias Standfest (Archilyse) spoke about their startups and the digitization of the building process. (Photo: Tanja Kernweiss)

There was much to discuss during the breaks (Photo: Tanja Kernweiss)

Moving PicturesJan Grarup gave a deeply moving lecture. In the past decades he has traveled with his camera to all the war and conflict zones around the world. His photos and reporting have appeared in magazines and newspapers around the world, including the biggest German-language periodicals. He won the World Press Photo Award eight times.

Grarup showed some of his photos and told the stories behind them. For example, he presented pictures he took during the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. His time there was the worst in his life, he recalled, filled with emotion. It still haunts him today. Among the pictures he brought along was one of a severely wounded girl who had suffered terrible head injuries from a machete attack. She barely survived. Her entire family was murdered. “I wonder what has become of her today,” the photographer said thoughtfully. “Is she a mother? Did she start a family?” He has been trying to find the girl ever since – so far in vain. Grarup also showed photos of children playing cheerfully in the war zones of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. They had sometimes been taken even though the area was under artillery fire. And he also had a picture of a laughing African girl with him, taken in a hospital ward. She had laughed at him, he remembered, because, as a totally sweaty white man, she had thought he looked “like a pig.” Children, he summed up, had a remarkable ability to master traumatic situations.

Jan Grarup giving his lecture; his lecture was an appeal to the architects present. (Photo: Tanja Kernweiss)

Grarup wanted his lecture to be understood primarily as an appeal to the architectural scene. He wasn’t at all interested in just shocking the audience. Currently, he said, more than 65 million people worldwide have been forced to flee their homes. According to the UNHCR, the figure was almost 70 million in 2018. Only a relatively small portion of them are in fact trying to reach Europe, he continued. Most wanted to remain at home and have hopes of being able to return soon. But for those who arrive in his homeland of Denmark, or in Germany or another European country, it is important to offer them quality living space and, above all, to promote their integration. “Of course we can’t change the world,” he said to the audience. “And I can’t build anything either. I’m just a photographer. But you can.”

World-Architects already supports the platforms “Architecture for Refugees” and “Architecture is a Human Right.” The former, in particular, serves to advance the discourse around the housing refugees. The question is, to what extent can architecture bring about integration and inclusion?

This article originally appeared as "Dicht, gross, aufrüttelnd – «Architecture Matters»" on Swiss-Architects. Translation by David Koralek / ArchiTrans.