The Aesthetics of a 'Concrete Utopia'

John Hill

3. septembre 2018

Miodrag Živković. Monument to the Battle of the Sutjeska. 1965–71, Tjentište, Bosnia and Herzegovina. (Photo: Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016)

Four years after Martino Stierli was named the Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York – he took over the post from his predecessor, Barry Bergdoll, one year later, in 2015 – we finally see a major exhibition from the Swiss-born historian and curator: Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980.

Well before it opened at MoMA in July, the symbol of Toward a Concrete Utopia was Miodrag Živković's Monument to the Battle of the Sutjeska (photo above), as presented in promotional literature and previews of summer exhibitions in New York City. The image of the two angular stelea perched in the snowy landscape hit a chord: architecturally daring yet vague in meaning, it was the right image for piquing the interest of fans of architecture but also of art lovers who frequent the NYC institution. It also foreshadowed how just over thirty years of architecture (1948-1980) in Yugoslavia would be presented by MoMA: through gray, moody photographs that would give pause and foreground the former country’s architecture as historically important. Therefore this review of Toward a Concrete Utopia focuses on the show’s appearance: in the specially commissioned photographs by Swiss photographer Valentin Jeck and the exhibition design itself.

Saša Janez Mächtig, K67 Kiosk, 1966. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The exhibition is located in the third floor galleries that were renovated by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) as part of their larger, ongoing reconfiguration of the mammoth and always crowded museum. During construction, visitors get their tickets next to the courtyard then ascend two floors via escalators or elevators to arrive at the exhibition. This means the first piece of Yugoslavian architecture they will see is the K67 Kiosk (photo above), situated by the escalators and bathrooms on the third floor. Doing so creates an internal paradox: are the designs in the show gray and existential like Monument to the Battle of the Sutjeska or colorful and optimistic like Kiosk 67? Ultimately, the architecture of modern Yugoslavia embodies these and everything in between, through a diverse range of designs that are ambitious and adventurous.

Found at one end of the first gallery: Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade, Belgrade Master Plan, 1949-1951. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The wall text at the entrance to the exhibition explains its political context: "Toward a Concrete Utopia focuses on the period of intense construction between the country's break with the Soviet bloc, in 1948, and the death of its longtime authoritarian leader, Josip Broz Tito, in 1980." The relevance to an architectural exhibition at MoMA is found in this accompanying statement: "Architects, designers, and artists played a key role in imagining the future of socialist Yugoslavia … the federation of six republics [Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia] and two autonomous provinces [Vojvodina and Kosovo] brought together by antifacsist struggle during World War II." Implicit in these statements are a sense of optimism following disaster and the country's dependence upon a singular figure. Although the country would host the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo in 1984, four years after Tito's death and six years after the International Olympic Committee's selection, ethnic strife and insurgencies would lead to the breakup of Yugoslavia into five successor states come 1992.

"Modernization" section with photo of Milan Mihelič. S2 Office Tower. 1972–78. Ljubljana, Slovenia. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Although political at its core, Toward a Concrete Utopia is an architecture exhibition and therefore relies upon the means of expression used by architects. In turn, hundreds of drawings, models, photographs, and films are organized into four sections: "Modernization," which examines the urbanization of the once rural country; "Global Networks," which looks at tourism and infrastructure at home and abroad; "Everyday Life," which explores mass housing and the designer goods that would fill them; and "Identities," which grapples with the country's regional diversity and overall unity. Further broken down into smaller parts, these sections are traced sequentially in a counterclockwise loop through a half dozen galleries and a few smaller adjacent rooms.

Andrija Mutnjaković. National and University Library of Kosovo. 1971–82. Prishtina, Kosovo. Exterior view. (Photo: Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016)

One of the most remarkable buildings in Toward a Concrete Utopia is the National and University Library of Kosovo (1982), encountered in the first section through an impressive model and some drawings and photographs. Designed by Andrija Mutnjaković as a clutser of small cubes illuminated by nearly 100 domes and shaded by metallic screens, the library was used by the Yugoslav army in the 1990s and emptied of much of its contents, though this century it has returned to serve its original purpose. As shown above, it is one of the buildings given the Valentin Jeck treatment. He captures the library below a swirl of gray clouds that lighten above the building's mountainous profile. Paradoxically, shadows cast across the muted grass in the foreground, combined with the illumination of the building's filigree facade, hint at the presence of the sun to the left of the frame – a parting in the gray clouds.

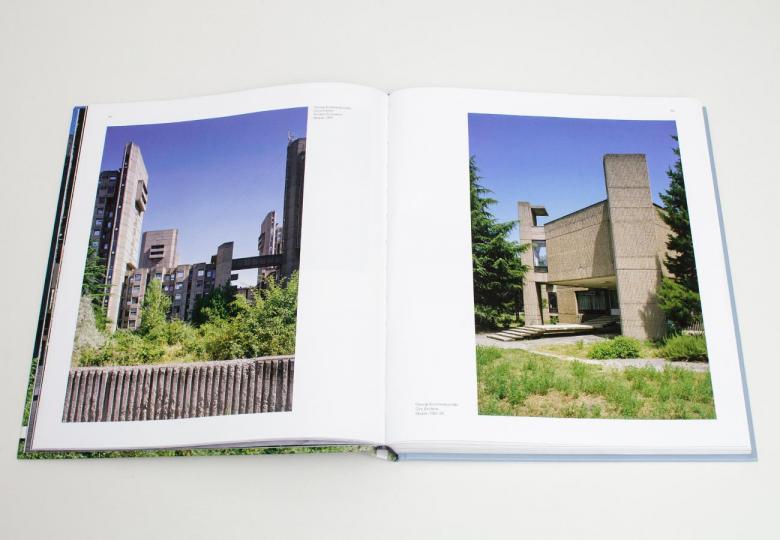

A spread from "Modernism In-Between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia" by Maroje Mrduljaš and Vladimir Kulić with photographs by Wolfgang Thaler. (Image: wolfgangthaler.at)

Looking at Jeck's photos of architecture in the exhibition, it's excusable to believe that cities from the former Yugoslavia are starved for sunlight. But that's hardly the case. A cursory glance at charts of sunlight duration reveals, for instance, that Belgrade, Serbia, sits in the top 15 of major European cities in terms of annual sunlight hours, with more than 2,100 per year. Belgrade's July is almost as sunny as Barcelona's, in fact, but its winters are considerably grayer. Jeck's photos appear to focus on this climatic flip-side, preferring the desaturated appearance of winter rather than the crisp blue skies found in the summer months. The latter is clearly evident in the photographs of Austrain photographer Wolfgang Thaler. He photographed Yugoslavian modern architecture for the 2012 book Modernism In-Between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia (image above), which happens to be co-authored by Vladimir Kulić, who curated Toward a Concrete Utopia with Martino Stierli. Although Thaler's images are more aligned with traditional architectural photography, with sunshine and blue skies, here they serve to illustrate how MoMA's specially commissioned photos intentionally went in a different, more dramatic direction to elicit particular reactions.

"Global Networks" section with model (by students from The Cooper Union) of Janko Konstantinov's Telecommunications Center, 1968–81, Skopje, Macedonia. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Moving through the exhibition galleries in the prescriptive counterclockwise rotation, the monochrome models, desaturated photos, and architectural drawings are presented across shifting colors of paint on the walls. There are grays, beiges, and greens, but also brighter shades of yellow, pink, and red. Far from groundbreaking, the colors nevertheless do a good job in orienting visitors within the exhibition's four sections and subsidiary parts, and they serve as a foil to Jeck's photos and the other artifacts that lean to the gray and monochrome. The strongest pop of color comes in the gallery devoted to "Everyday Life," which has the exhibition's most diverse presentation: photos and drawings, to be sure, but also furnishings in the center of the room and a wall of screens displaying clips from films and TV shows set in the socialist housing blocks. Jeck's photo of one of these, the Braće Borozan building block in Split (photo below), is beautiful, but it's hard to be optimistic about the everyday lives behind those primarily solid walls. Perhaps the televisions, chairs, and other objects served, like the Kiosk 67, as colorful antidotes to what's depicted in the exhibition's photos as dour surroundings.

"Everyday Life" gallery. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Dinko Kovačić and Mihajlo Zorić. Braće Borozan building block in Split 3. 1970–79. Split, Croatia. Exterior view. (Photo: Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016)

The last section, "Identities," is where we encounter such architectural statements as the Monument to the Battle of the Sutjeska, but it's also where we also find, as the section makes clear, names both familiar, such as Jože Plečnik, and lesser known, such as Juraj Neidhardt and Bogdan Bogdanović. While Plečnik is limited to one project (most of his work in Slovenia was carried out before the period of the exhibition), the last two are given whole rooms to themselves. Like the yellow of "Everyday Life," the rich green and red of Neidhardt's and Bogdanović's small rooms (photos below) immerse visitors into the designs they produced.

"Identities" section at end of gallery circuit, with views into Neidhardt and Bogdanović galleries on the left. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Gallery devoted to Juraj Neidhardt. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Gallery devoted to Bogdan Bogdanović. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

It's fitting that the last image encountered by visitors before they walk through the exit doors of Toward a Concrete Utopia is Miodrag Živković's Monument to the Battle of the Sutjeska (photo below). It is accompanied by other monuments, such as the Monument to the Uprising of the People of Kordun and Banija (photo at bottom), which also sits in a snowy landscape beneath a gray sky. Monuments are works of architecture that veer toward art by being free from function beyond expression and meaning, so it's no wonder that MoMA has latched upon them in the exhibition and its promotion. These architectural forms exhibit a time of free expression and belief in the power of architecture (and architects) to give meaning and solve problems. The era was geographically and politically unique, and it produced some of the most exciting, yet relatively unknown, architecture produced last century. Many visitors wouldn't have known otherwise if not for MoMA's ambitious, must-see exhibition.

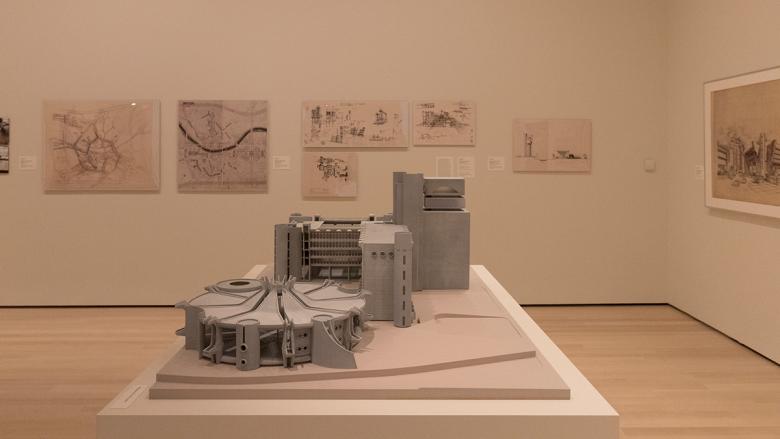

Installation view of "Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980," The Museum of Modern Art, New York, July 15, 2018–January 13, 2019. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art. (Photo: Martin Seck)

Berislav Šerbetić and Vojin Bakić. Monument to the Uprising of the People of Kordun and Banija. 1979–81. Petrova Gora, Croatia. Exterior view. (Photo: Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016)

Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980 is curated by Martino Stierli, the Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, the Museum of Modern Art; and Vladimir Kulić, Associate Professor, School of Architecture, Florida Atlantic University, Fort Lauderdale; with Anna Kats, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Architecture and Design, the Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition is on display at MoMA from 15 July 2018 to 13 January 2019.

Articles liés

-

The Aesthetics of a 'Concrete Utopia'

on 03/09/2018