6. luglio 2022

Enzo Enea (Photo: Martin Rütschi © Enea Landscape Architecture)

Enzo Enea is a new type of landscape architect, sometimes filling the landscapes he designs with plants from his own arboretum in Switzerland. Ulf Meyer visited Enea at his office and tree museum in Rapperswil-Jona, southeast of Zurich, speaking with the landscape architect about his design ethos and learning about some of Enea Landscape Architecture's projects.

With climate change on many people’s minds, landscape architecture is also changing. Traditionally it was seen as a secondary design discipline, its job to fill empty leftover spaces between buildings. In central Switzerland one landscape design practice has grown in size and prominence with an international scope and unusual depth of design and execution — it has the potential to change the way people look at landscape architecture. Enzo Enea founded his eponymous firm in 1993; today it employs around 240 people, an unusually large number by European standards.

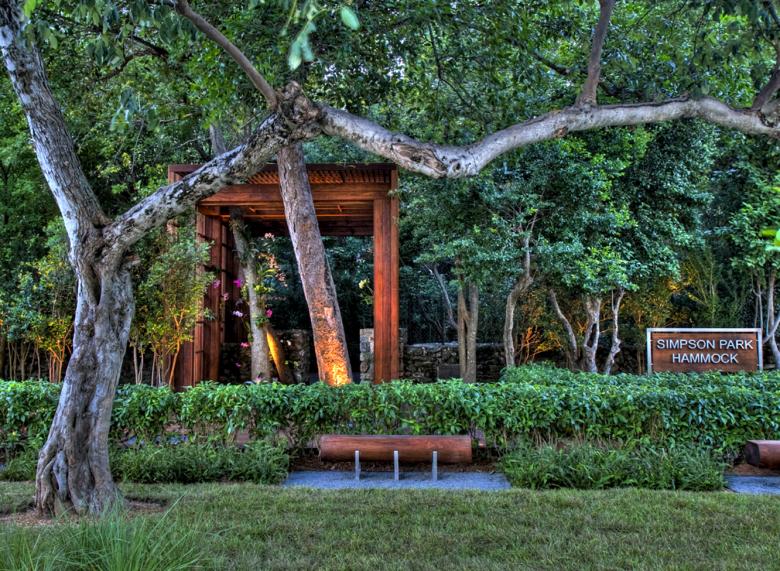

Enea looks at the contributions his garden designs can play in terms of ventilation, oxygen supply, and the lowering of temperatures on and around buildings. Still, aesthetics is as important to his firm’s work as performance. A case in point is Simpson Park in Miami, Florida, where a deep hammock of native plants and other elements extends to the sidewalk. A timber structure designed by architect Chad Oppenheim forms the entrance to the tropical grove. The entrance presents visitors with native plants that Enea planted as an “urban wild” or "passive park," as the Swiss-Italian designer calls it. The patch of nature was set aside in 1913 to preserve the last tracts of this tropical hardwood hammock, and as such Simpson Park is home to more than a dozen endangered species.

Simpson Park, Miami (Photo courtesy of Enea Landscape Architecture)

These hardwoods are also used for terraces and decks in other projects, including Park Grove, also in Miami. Here, Enea connected three residential towers designed by OMA with a tropical park and an “amenity deck,” visually blending four pools with the nearby Biscayne Bay. The roof landscape — a lush landscape akin to the Florida coastline with its leafy forests and palm shaded shores —creates a continuous grove over tiered amenities including storage, wine cellar, gym, and a screening room. Known for an ability to craft livable outdoor spaces that blur the boundary between a building and its surrounding landscape, Enea aimed for “harmony between tower and the coastal landscape.” The park forms a pathway from the tower to the bay, the developers claim, as a “physical and spiritual link from life in the tower to life on the water.”

Enea had worked in Hawaii before, experimenting with native species and learning the nuances of landscaping in a range of climates and ecosystems. Enea is also a tree specialist and collector. The Enea Tree Museum, a wonderland near Lake Zurich, showcases 50 trees saved from felling, some of which are more than 100 years old. The preservation of existing trees is a priority for him and native species have been protected and highlighted in Enea’s designs. “Sustainability along with beauty” is at the forefront of his work. His ability to blend landscape, botany, art, architecture, and design results in environments that feel rooted in their place. Fluid transitions lead from the airy residences at Park Grove to the gardens, for instance, where there is little definitive separation between indoors and out. In the luxury towers residents can entertain on their balconies or meet for cocktails at the rooftop pool. There are also outdoor fitness spaces, play areas for children, “nooks to uncover,” and “spaces in which to steal away,” as the developers describe them.

Park Grove, Miami (Photo © Robin Hill)

Enea’s work is defined by a respect for the history of a place and the relationship between the built environment and nature. His gardens can provide a sense of escape but also a feeling of intimacy and protection. In order to be able to find the most suitable trees for a new project, he sends out “tree scouts” that will look for available trees in the region.

For the Carré Belge in Cologne, Enea developed a landscaping system together with ingenhoven architects, who turned a former movie theatre and TV studio into a hotel. The building now acts as a stepped pyramid and green lung for the city with its tree terraces. The inner courtyard, too, provides shade to regulate humidity and to absorb dust and noise.

Carré Belge, Cologne (Photo: HGEsch Photography © ingenhoven architects)

In New York, Enea is currently redesigning one of the city’s most iconic outdoor spaces: Rockefeller Center’s sunken plaza, where, since 1936, the famous ice skating rink has attracted millions of tourists in winter months into the very center of the complex. Providing a sense of privacy and enclosure, I. M. Pei once praised the plaza as "the most successful open space in the United States." Enea’s design is adaptable to the seasons, with trees that will be literally moveable, providing shade in the summer and giving way to ice skating in the winter.

Rockefeller Center, New York (Visualization: Enea Landscape Architecture)

Away from big cities, Enea works on small, private gardens, such as for a holiday house on the Greek island of Kea. The house, designed by Christos Vlachos, was built with hammered natural stone blocks in the style of the island. The steeply sloping ground makes great views of the sea possible from any room in the house or spot in the garden, but the lack of rain and groundwater and the winds from the sea were a challenge. Big trees and walls reduce the winds. The use of gravel, wood and stone instead of lawn minimizes the need for irrigation.

Villa on Kea (Photo courtesy of Enea Landscape Architecture)

These different scales illustrate Enea’s versatility. Enea has offices in New York, Zurich, Miami, and Milan, and he has worked with such famous architects as Zaha Hadid, Bjarke Ingels, Tadao Ando, and David Chipperfield. While the office focuses on commercial, hotel, and residential buildings, Enea has also designed vineyards, a beer garden, even a whole “village” (Oaks Prague, in the Czech Republic).

Enea is famous as a savior of trees that would otherwise get cut down. Some of the old trees he has saved can be found in the Baummuseum outside of his office in Rapperswil-Jona. This tree museum, which anybody can visit for a fee, illustrates Enea’s approach and his biography. When he inherited his father’s business of importing Italian planters and troughs in 1993, he soon leased a big piece of land from the Mariazell Monastery and added a tree museum, nursery, and arboretum. When road construction or inner-city projects makes the felling of precious trees unavoidable, Enea enters the scene and uses his special knowledge for carefully taking trees out of the ground and relocating them to his grounds. There, sandstone walls at monumental scales combine with vegetation in a display of Italian sensitivity.

Enea Tree Museum, Rapperswil-Jona (Photo © Enea Landscape Architecture)

Enea’s karate master taught him such Japanese techniques as cutting roots. From small bonsais, he “scaled up” the techniques up for bigger trees. Today, Enea runs an in-house joinery and has experts for lighting and water. Described as “intuitive and direct,” Enea still designs all of the firm’s projects himself.

As a young man, Enea had learned to combine “the precise and the playful.” For him trees are not only a source of oxygen and vitamins, they can also counter the urban heat island effect. His designs aim for well-being as much as ecological benefits. “Mother Earth nourishes us,” he says. But cultivation is necessary. The tree museum helps make his visitors “more sensitive” toward trees, landscape elements which he sees as “integral, not decorative.”

While Enea usually starts with trees as a design element, he can adapt to different styles in different places. He has worked with many famous architects so, to him, “no architectural style is foreign.” Yet, the common denominator of all his designs is finding a solution for the genius loci and looking at the perimeter of the buildings. “My designs must fit the location and architecture,” no matter if they are large or small, open or closed. He seeks “peace and proportion” and consistent details. Sometimes he will work with a local botanist to “understand the place” even better, including the changes that come with the passage of time.

Enea Tree Museum, Rapperswil-Jona (Photo © Enea Landscape Architecture)

Like in the Japanese “Shiki” tradition, gardens should look different in color, fruit and scent in all of the four seasons. Rather than “sprinkling parsley onto somebody else’s potato,” Enea believes that the urban and landscaping plan should come first, and then the building. “That would be ideal,” he says. “Architects are always requested first, but that is a pity. Working together at eye level and from early on is the ideal setup, since landscape architects are not mere suppliers.” Still, he feels like he has to “fight for every square meter of green space.”

Enea’s office is big, but he wants to maintain a consistently high quality. Nevertheless, expanding across the Atlantic is something he has enjoyed, especially the challenge of working with tropical species in Florida. Now, he works on up to 100 projects per year, but he still insists on site visits to “read the place.” From a big university campus to a small private terrace, Enea will design with the same passion, even venturing into furniture and interior design. Enea thinks of his office as a "production company that also builds." It only rarely participates in tenders or competitions. The designs are made in Switzerland, but “languages, contracts, and cultures are different everywhere,” and that makes each project unique.

Enea Tree Museum, Rapperswil-Jona (Photo © Enea Landscape Architecture)

Enea’s career started with root pruning, when he observed that “to be cut like a bonsai is no fun for trees.” He has grown to connect outsides and insides of buildings and create what he calls “picture spaces” of all sorts. Enea still is a tree man; it is most important to him that he determine the planting of trees. Furthermore, the symbolic importance of trees for him is that they seem to say “You can't buy time!” A lack of patience to see a plant grow is one deficiency in our society, but Enea also sees other issues, including the omnipresent soil compaction in cities working against his goals of biodiversity and comfortable microclimates.

“We do not need just further technical development,” he says. “When people fly to Mars, while others still do not have enough drinking water, things fall apart.” But he never wants to act as if he is morally superior. “Rather,” he says, “we can communicate sensitive approaches to nature by showing beauty like the church once did.” With his growing office headquartered on the land of a former monastery, he does not seem overwhelmed by his own success. Rather, he is ready for more decades of new landscape designs.