Michael Blackwood, 1934–2023

John Hill

2. 4月 2023

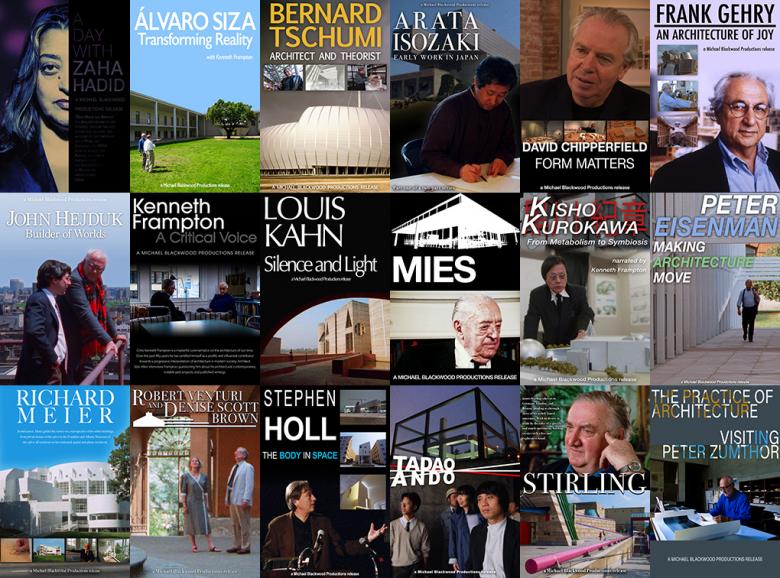

From Ando to Zumthor: some of the big names in architecture documented on film by Michael Blackwood. (Cover photos via Michael Blackwood Productions)

Filmmaker Michael Blackwood, who directed and/or produced over 150 documentary films, most of them focused on artists, architects, and musicians, died on February 24 at the age of 88.

We learned about the death of Michael Blackwood in last week's obituary in the New York Times. Richard Sandomir's obituary focuses primarily on the profiles of famous artists (Isamu Noguchi, Christo) and musicians (Thelonious Monk, Philip Glass) made by the German-born filmmaker over his roughly 60-year career. Yet Blackwood had a strong appreciation for architecture as well, as evidenced by the 46 architecture documentaries listed at Michael Blackwood Productions, the company he established in 1982. Nevertheless, only two paragraphs in the Times obituary — or 85 of its 1,140 words — address the films on architecture made by Blackwood, saying, in part: “His fascination with architecture led him to make films about some of its stars, including Louis Kahn, Richard Meier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Peter Eisenman and Frank Gehry.”

Blackwood's first film, Broadway Express, was a 20-minute portrait of the NYC subway at night, made in 1959, ten years after he and his family emigrated to the United States from Germany. (He was born Michael Adolf Schwarzwald on July 15, 1934, in Breslau and changed his name when he became a US citizen in 1955.) After heading back to Germany to direct TV documentaries, Blackwood returned to the US in 1965 and established Blackwood Productions; his brother, Christian, who also carried the Blackwood name, joined the company in 1972. The pair made numerous films together, including two about Thelonious Monk, but they split professionally in 1982, the year Michael established his eponymous production company. (Christian died in 1992.)

One year later, in 1983, Michael Blackwood released his first documentary devoted to architecture: Beyond Utopia: Changing Attitudes in American Architecture. The one-hour doc is described as a discussion of “the postmodernist movement through its meaning and motives” and is structured as a portrait of a few of its practitioners who were considered protégés of Philip Johnson: Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Frank Gehry, Michael Graves, and Peter Eisenman. The cinéma vérité aspect of Blackwood's filmmaking is humorously evident early in the film, when the first words viewers hear from Eisenman, the "controversial" theorist and architect, come as he is getting his hair washed in a Manhattan salon. In the next scene Philip Johnson states “we are all whores in this business” before the Chippendale top of the AT&T building is shown under construction.

Trailer for Beyond Utopia: Changing Attitudes in American Architecture

The last architecture films directed by Blackwood were Greg Lynn: Archaeologist of the Digital and The New Clark: Bringing the Ando Experience to the Berkshires, both released in 2014. In between Beyond Utopia and these last two docs, Blackwood made dozens of documentaries on architecture, most of them serving as portraits of individual architects (see image at top), but some of them documenting exhibitions and conferences (the latter especially at Columbia GSAPP), a few capturing stylistic and regional trends in the profession, and a few focused on educators and critics. They are an important record of three decades of architecture in the US, Japan, Germany, and other parts of Europe — decades that saw architecture go through numerous isms, gain some attention in the mainstream, and earn some of its practitioners celebrity status.

Yet, even as architecture blossomed in the years and decades before and after Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao opened in 1997, a time when documentary films also exploded in popularity, Blackwood's films were little seen: “The audience for the films came exclusively from university and college libraries which ordered hard copies,” according to his son, Benjamin, “with limited televised runs in select European countries.” (This architecture-educated writer who remembers watching a few in undergrad can attest to that fact.) Gladly, the situation has changed in recent years, as the production company now run by Benjamin has been digitizing and remastering the docs and making them available via streaming services including Kanopy and Shelter. Although Blackwood's son hopes the wider catalog of films will inspire artists, the architectural documentaries are most valuable as time capsules of architecture's postmodern age, when the issues the profession and academia grappled with increasingly played out in public and through the media. Perhaps the greatest influence of Michael Blackwood's architecture films will be on new generations of filmmakers documenting architecture in spoken words and moving images.