'In Our Time' at The Met (and a detour to Engadin)

John Hill

12. 2月 2019

Inside Muzeum Susch in Switzerland's Engadin region (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

On January 19, 2019 – a chilly Saturday – seven hundred people packed into the Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art for In Our Time, a day-long celebration of the best buildings and “inspiring architectural ideas” from 2018.

It was the third In Our Time: A Year of Architecture in a Day, the brainchild of Beatrice Galilee, architecture and design curator at The Met. It was my first time attending the annual event, though I could tell when approaching the line snaking down the steps in front of the museum before its 10 am opening that the symposium would be a crowded one. A fair number of the people waiting in the cold just looked like architects, probably eager to get a seat before the others who snagged free tickets. The long line inside reiterated my first impression, as did the 700 attendance number thrown out by The Met’s Maricelle Robles (co-organizer of In Our Time with Galilee) at the beginning of the morning session. Later on I learned that dozens more were still waiting in line, hopeful for seats to open up; that an overflow room downstairs from the auditorium broadcasted the event to even more ticket goers who couldn’t get a seat; and that more than 10,000 people watched In Our Time live on The Met’s Facebook page. What all this means, simply, is that architecture has a substantial, captivated audience; it also raises the obvious question: Why doesn't The Met hold architecture events more often?

Carla Juaçaba Vatican Chapel (Photo: Federico Cairoli)

Starting at 10:30 am and ending at 6:30 pm, In Our Time was eight hours of nearly wall-to-wall architecture: ten presentations, two short films, one conversation, one panel discussion, and one keynote lecture partitioned into morning and afternoon sessions. The bulk of the enlightening, though sometimes grueling, day was taken up by the “Projects of the Year,” which consisted of twelve projects – six completed buildings, two temporary pavilions, two short films, one piece of conceptual architecture, and one sculpture – presented in two halves in the morning and afternoon. An apparent hybrid of short, Pecha Kucha-style presentations, TED talks, and lectures at schools of architecture, the one-way, no-Q&A presentations were notable for the quality of their projects though just as much for their diversity. Given the various project types beyond buildings, the many geographies (11 countries on 5 continents), and the mix of creators (9 men and 4 women), the curated selection of projects pointed to diversity as a signal of importance rather than the discovery of any overriding area(s) of concern for architects in the previous year.

"The Mile-Long Opera: a biography of 7 o'clock," which took place on the High Line in October 2018 (Photo: Iwan Baan)

To give a sense of this impression, here is the way the afternoon “Projects of the Year” played out, coming after Galilee’s discussion with architect Elizabeth Diller and composer David Lang about The Mile-Long Opera (a great talk that made me even more upset at missing the event). First, Jing Liu of SO-IL presented the offbeat vernacular of their North Fork House on New York’s Long Island and then artist Michael Rakowitz traced his infatuation with Iraqi dates to The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, his recreation of an ancient Iraqi sculpture made with date syrup cans and perched on a pedestal in front of the National Gallery of Art in London. Architect Carla Juaçaba talked briefly about her skeletal Vatican Chapel from last year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, and then came a screening of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s meditative film, Blue, which didn’t appear to have any relationship to architecture other than the filmmaker having trained as an architect. OMA’s only female partner (a fact she mentioned relative to the commission's geography and politics), Ellen van Loon, presented the Qatar National Library, and then finally Freddy Mamani, through a translator, walked the stunned audience through a few of the more than sixty exuberant, colorful buildings he has built in El Alto, Bolivia. (Somebody a couple rows ahead of me exclaimed after his presentation, “I’m so on the next plane to Bolivia!")

Freddy Mamani's "New Andean Architecture" (Photo courtesy of The Met)

The afternoon “Projects of the Year” were followed by a panel discussion, In our Future—Design in a Post-Human Age. The four panelists offered much to ponder about technology, labor, the planet, and their relationships, but it came across, like Blue, as only marginally related to architecture. (I felt transported to a symposium on art, or technology, or art & technology.) In his closing keynote, Eyal Weizman described in minute details how his firm, Forensic Architecture, uses the tools of architecture (e.g., open source CAD software and aerial imagery) to aid human rights organizations in their attempts at social justice. With architectural training applied to the investigation of buildings destroyed by violence rather than to the design of new buildings, Weizman’s work was a fitting end to eight hours ping-ponging between traditional and atypical architecture. But for this writer it was a project in the morning – one clearly on the traditional end of the spectrum – that caught my attention more than anything throughout the day: a museum in Switzerland I would visit just three weeks later.

Muzeum Susch sits hidden (it's in the white buildings to the right of the church tower) in Susch, a village of 200 in Switzerland's Engadin region. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Designed by Chasper Schmidlin and Lukas Voellmy of Zurich’s Voellmy Schmidlin, Muzeum Susch is part adaptive reuse, part new construction, and part “found” cave-like spaces, all linked together into one whole. Open since January 2, 2019, in the small village of Susch in Switzerland’s Engadin Valley, the museum is the brainchild of Polish art collector Grażyna Kulczyk (hence the “z” in Muzeum), who focuses "not exclusively" on woman artists and art that "has been at times overlooked or misread." During In Our Time Schmidlin and Voellmy described their strategy of retaining as much as possible the complex of medieval buildings it occupies, integrating site-specific artwork into the spaces, and elevating the importance of in-between spaces. But it was clear from the photographs and drawings they showed that Muzeum Susch must be visited to be understood and appreciated. So that’s what I did. The photos and captions that follow document my visit – one every architect should take if they find themselves in Switzerland.

Muzeum Susch is housed in a complex of medieval buildings next to the Inn River that were first used as a monastery then, centuries later, as a brewery and other uses. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

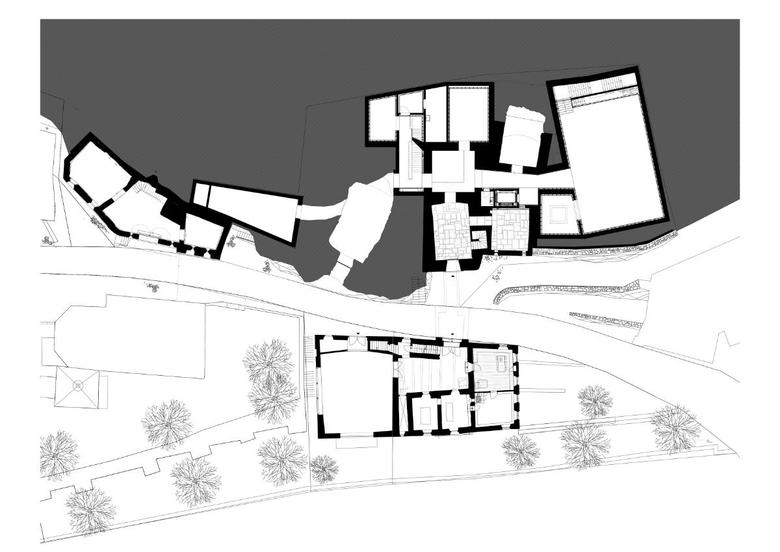

Muzeum Susch's galleries occupy two buildings – Building A, Bieraria Veglia, at bottom and Building B, Bieraria, at top – that are linked by a tunnel under the road and expanded by new galleries carved into the earth. (Drawing: Voellmy Schmidlin)

In the base of Building A is the entrance, off of which are small rooms with some of the museum's many site-specific artworks. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

One room, for instance, features Adrián Villar Rojas's totem-like "From the Series The Theater of Disappearance XXXI" (2018). (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Elsewhere off the lobby, a shaft of light cuts through the 12th-century medieval building. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

In the center of Building B is Monika Sosnowska's site-specific "Stairs" (2017). (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

"Stairs" vertically extends four floors to figuratively connect the different levels of Building B and act as a wayfinding device for the informal layout of galleries around the shaft of space. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

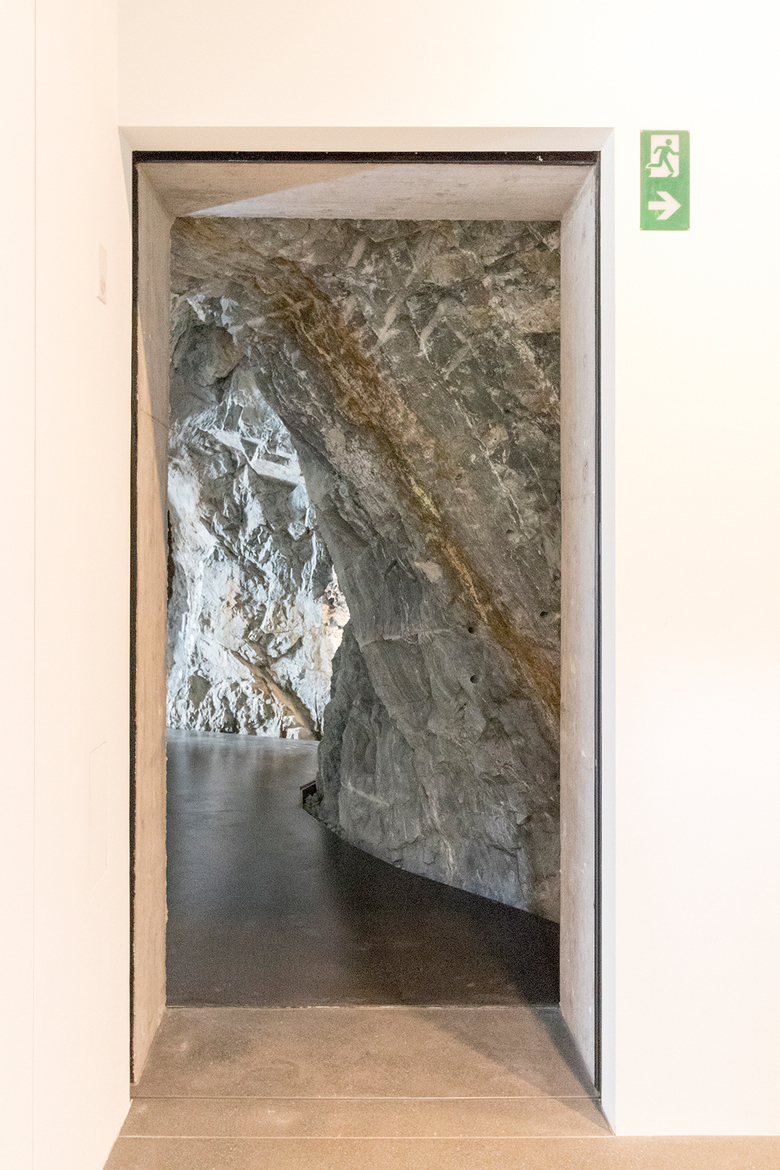

A doorway near the base of "Stairs" leads to one of Muzeum Susch's most thrilling rooms... (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

...where Mirosław Bałka's site-specific "Narcissussusch" (2018) is situated. A stainless steel cylinder slowly rotates in the middle of the found grotto. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The new rooms in Building B include more conventional gallery spaces for displaying art. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Moving vertically through the building means confronting Sosnowska's "Stairs" every so often. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Some of the gallery spaces are a clever mix of old and new, as in the rock on the opposite side of the wall in the above photo (note "Stairs" visible through the opening). (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Other galleries are more traditional in feeling, with exposed wood structure and small windows with views of the village and the surrounding landscape. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Panoramic views can be had from the auditorium above the entrance back in Building A. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Upstairs from the auditorium is a reading room, replete with wood surfaces... (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

...and an adjacent library with plenty of space for the accumulation of books. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The creativity of Muzeum Susch's art and architecture is expressed subtly on its exterior, as in the doors to the auditorium designed by Voellmy Schmidlin. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

This last view of Muzeum Susch is the inverse of the photo at the top of this article: a window to the street reveals Mirosław Bałka's "Narcissussusch" to passersby. Muzeum Susch – and the art it contains – won't be hidden from the world for very long. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

関連した記事

-

'In Our Time' at The Met (and a detour to Engadin)

on 2019/02/12