Cave Bureau, Kenya’s most exciting architecture office

Through the Door of No Return

Photo: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art / Kim Hansen

The sixth and final exhibition in the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art’s “The Architect’s Studio” series presents the Kenyan architectural studio Cave Bureau (stylized as cave_bureau), founded by Kabage Karanja and Stella Mutegi in Nairobi in 2014. Ulf Meyer finds it a fitting end to a remarkable series.

In the show at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art north of Copenhagen, cave_bureau takes visitors back a million years to the landscapes that were “the setting for the origins of humankind,” as the studio puts it, before the era of the Anthropocene or “the architecture that the very first people knew.” The Anthropocene is defined as the era in which humankind’s influence on nature is now all too visible. Cave_bureau base their work on the volcanic caves around Nairobi, the cradle of mankind where the first hominids lived. Later, slaves and Mau Mau freedom fighters also passed through these caves, making them the symbolic place for the darkest hour in Kenyan history as well as the place where the modern nation was born. The volcanic caves around Nairobi contain testimonies to Kenya’s history. For a local audience, a special cultural connection comes from knowing Danish author Karen Blixen worked in Kenya for seventeen years.

Stella Mutegi and Kabage Karanja (Photo: cave_bureau)

The Kenyan government plans to use the area around the caves in the Great Rift Valley as a big geothermal plant, with great consequences for nature, animals and humans, especially the Maasai. Specifically, as part of Kenya Vision 2030, the European Investment Bank has invested $95 million to drill 630 geothermal steam-production wells to generate 5,530 MW of geothermal power. This “green revolution” runs counter to the area’s indigenous culture, which “has been living most sustainably for centuries,” Karanja and Mutegi note, “and consuming the lowest amount of CO2.” Cave_bureau seeks “to reveal the inequality that accompanies green energy transition.”

Shimoni Slave Caves (Photo © cave_bureau)

Under the title Anthropocene Museum, Karanja and Mutegi formulated the foundation for cave_bureau in 2014, after both were let go from their normal jobs as architects in a big commercial office. Actually, the two still design concrete skyscrapers and luxury housing estates in Nairobi, but in the exhibition they “hide their sins” and therefore do not mention this other work. For them, doing large commercial and traditional architecture projects is a financial prerequisite for doing culturally or sustainably minded projects. That is not the ideal situation, though, as connecting their talent and knowledge in one realm with the commercial design tasks in clever ways would be much more fruitful.

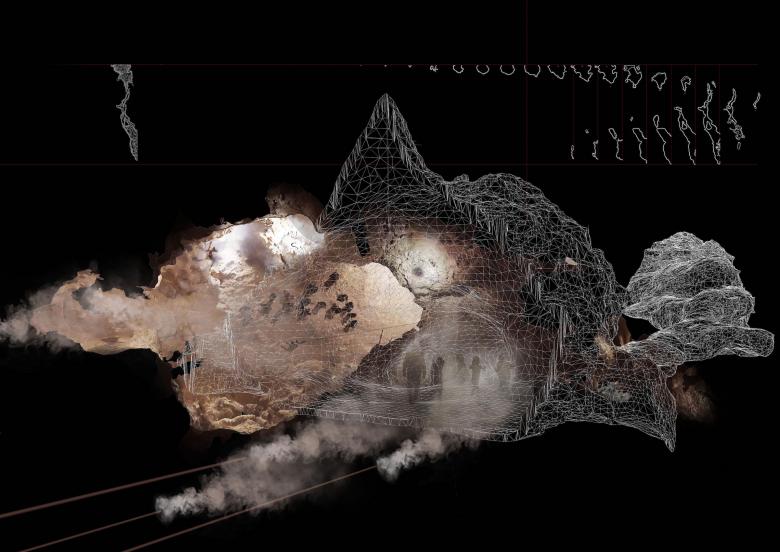

Cave_bureau, “Of Steam and Struggle” (Drawing © cave_bureau)

The entrance to the exhibition is a version of the gate through which enslaved people from West Africa passed before departing by ship for distant shores. In the exhibition, the architects have enlarged this gate — The Door of No Return — and transformed it into an installation of stalactites made with limestone quarried in Faxe, Denmark. While the reference to this important and unfortunate part of history is touching, it refers to the history of distant West Africa, from where slaves were shipped to the Danish West Indies; in Kenya, in East Africa, the slave trade served the Arab world.

The first room features the Anthropocene Museum, displayed through little installations and interviews in short films. An installation about the volcanic caves features models that compare the caves to the history of Western architecture. A fascinating observation from them finds the (subtractive) “architecture that the very first people knew,” as cave_bureau calls the caves’ collapsed roofs, has some resemblances to the Pantheon in Rome. Although the connection to Gottfried Semper is not made, it is there. Semper argued in his pioneering treatise, The Four Elements of Architecture, that the threading, twisting and knotting of linear fibers were among the most ancient of human arts, from which all else was derived, including both building and textiles. “The beginning of building,” he declared, “coincides with the beginning of textiles,” and the fundamental element linking the two was the knot.

Installation view showing volcanic crater in the foreground and Pantheon/cave collage in the background. (Photo: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art / Kim Hansen)

Cave_bureau has 3D-scanned the caves and used them as a model for their architecture. For the exhibition, Karanja and Mutegi wanted to depict the caves at a scale of 1:1 but doing so with something 3D-printed would have been odd. To release the “traumatic elements of history” found in the caves, they needed a representation. Phil Ayres and his students at the Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen found a way to hand-weave the shape of Shimoni Cave as a tri-hexagonal rattan structure in full-size.

The reproduction of the spaces of the caves is stunning. Even though the architects claim that it was “inspired by pre-colonial craftsmanship,” the IT and architecture lab at the Academy chose Indonesian material and a Japanese technique, called Kagome. A sophisticated program allowed the transformation of shapes into a weaving pattern with 5, 6 or 7 corners to create double curvatures (convex and concave). It is not unlike some of Shigeru Ban’s buildings, such as the Centre Pompidou-Metz or the Heasley Nine Bridges Golf Clubhouse in Yeoju, South Korea.

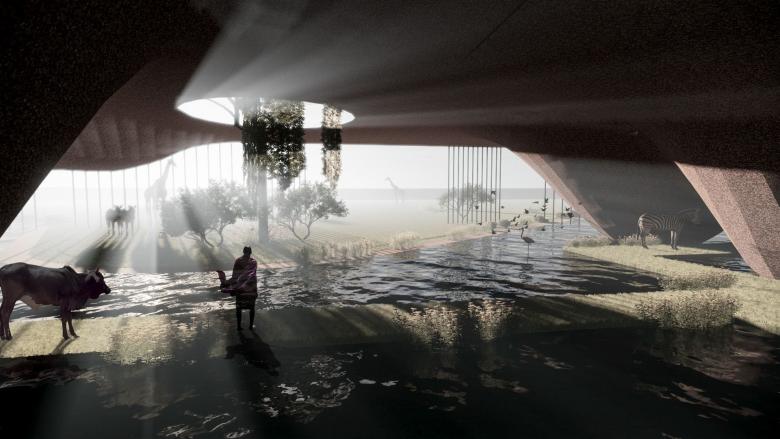

Antropocene Museum 4.0, Maasai Cow Corridor, 2021 (Visualization © cave_bureau)

For cave_bureau, sophisticated 3D scans of the caves, or “nature’s own architecture,” act as a model for new designs, including the proposed Cow Corridor, a restoration of Maasai grazing routes through Nairobi. The British rulers of the city had closed the city for pastoral migration in 1880. What material would the massive Cow Corridor be made of? The architects are hesitant to define it. In that sense, the research and design approaches fall apart.

The “cave” installation was hand-woven, a task that took six people three months. While the material and technique are unfortunately unrelated to Kenya, it is also disappointing to learn that neither the architects nor the curators have thought of a clever way to reuse the beautiful screen after the exhibition.

Installation view showing top of hand-woven “cave” installation (Photo: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art / Kim Hansen)

The Architect’s Studio: Cave_bureau concludes the series of architectural exhibitions curated by Kjeld Kjeldsen that started in 2017 with Wang Shu and Amateur Architecture Studio, and subsequently presented the studios of Alejandro Aravena, Tatiana Bilbao, Anupama Kundoo, and Forensic Architecture. It is a fitting end to what might well be the best architecture exhibitions produced in European museums in the last decade. It picks up on a strand also taken up by this year’s Biennale in Venice: 2023 is the year the European architectural scene focused on Africa’s emerging designers.

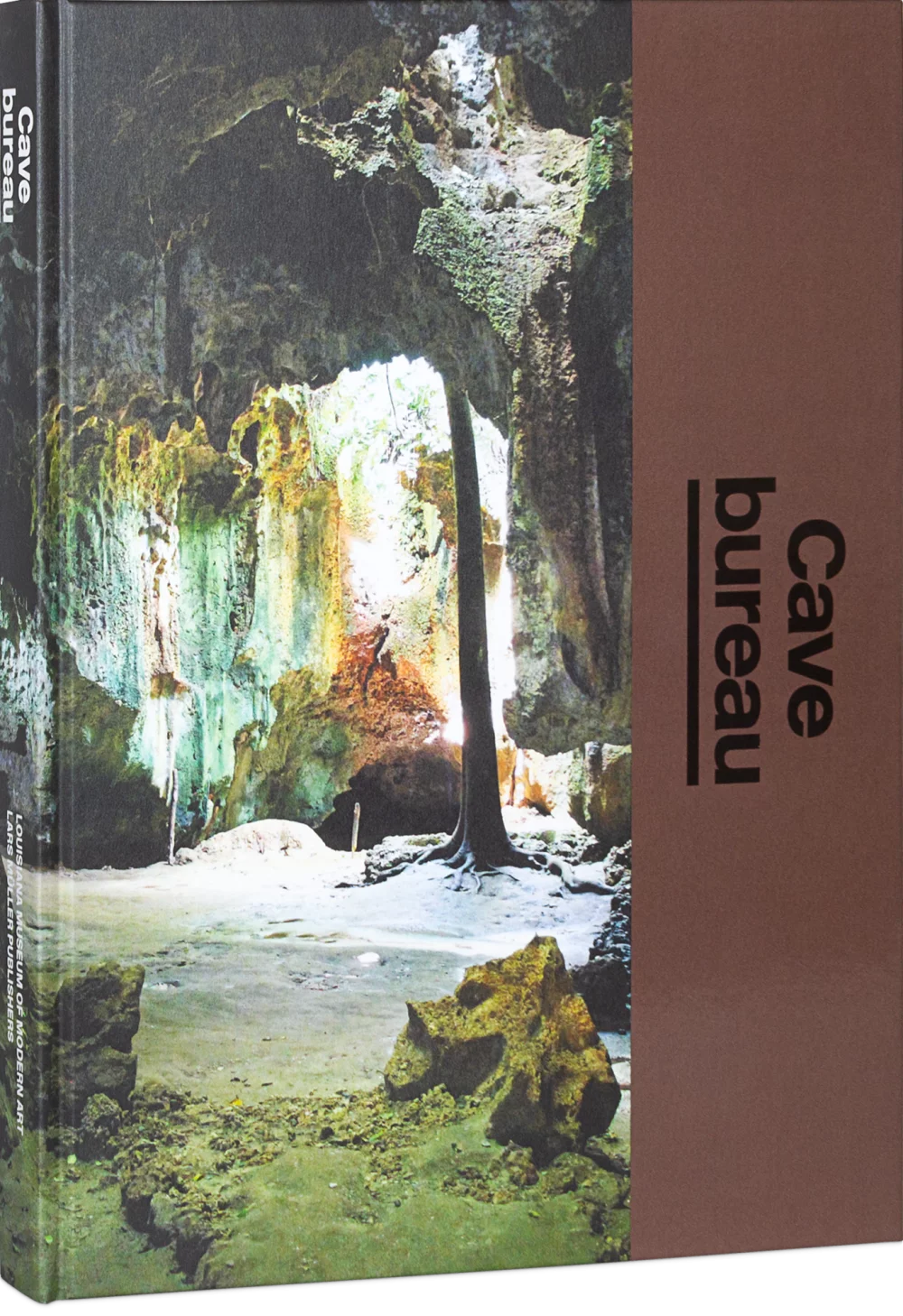

The accompanying catalogue features an introduction by Mette Marie Kallehauge, Kjeld Kjeldsen and Poul Erik Tøjner; articles by Kabage Karanja, Stella Mutegi, András Szántó, Mark Williams, Jan Zalasiewicz, Molly Desorgher, Kathryn Yusoff, Joy Mboya, Ngaire Blankenberg and Lesley Lokko.

“Cave_bureau: Spaces of Trauma, Spaces of Healing” documentary by Louisiana Channel

Cave bureau: The Architect’s Studio

Edited by Mette Marie Kallehauge, Malou Wedel Bruun, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

24 × 30 cm, 9½ × 11¾ in

208 Pagina's

179 Illustrations

Hardcover

ISBN 9783037787311

Lars Müller Publishers

Purchase this book