Designing with Solid Wood

John Hill

22. juni 2015

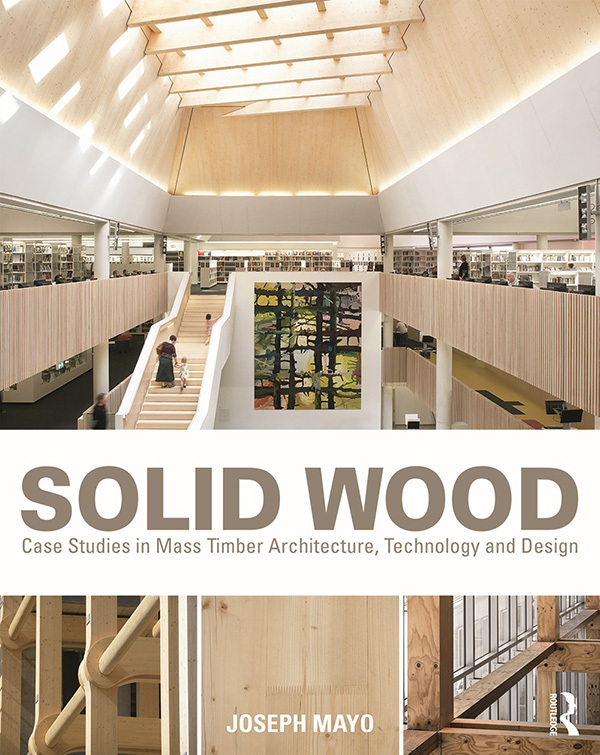

Helen & Hard: Vennesla Library (Photo: Emile Ashley)

With a growing awareness of the environmental benefits of solid wood over steel and concrete construction, more and more buildings this century are being constructed out of wood. With over twenty case studies in Joseph Mayo's new book, Solid Wood, World-Architects spoke with the architect and author about a handful of them.

Mayo, an architect at Mahlum Architects in Seattle, wrote the book after winning an Emerging Professionals Traveling Scholarship in 2011. Sponsored by the local AIA chapter, the annual scholarship asks entrants to focus on issues relevant to the Seattle design community. Seeing Kaden + Partner's E_3 housing project in Berlin, and considering the potential for similar construction in the well-forested Pacific Northwest, Mayo became interested in timber systems and decided to look at innovations in solid wood construction in Europe for his winning scholarship. Following his travels, which consisted of visiting buildings but also speaking with architects and others involved on the projects, he lectured and then put up a gallery show in Seattle. Later, seeing that most books on the subject were more eye candy than useful technical advice for architects, Mayo wrote Solid Wood: Case Studies in Mass Timber Architecture, Technology and Design, which was recently released by Routledge.

While obviously geared toward architects, given the voluminous technical advice in its pages, Solid Wood is hardly an esoteric read. Following an introductory section where Mayo gives a short history of building in wood, speaks about the carbon-sequestering benefits of mass timber construction, details various solid wood materials and concepts, and addresses concerns of building with wood (structure, fire, etc.), he then presents the case studies in eight geographical chapters: England, Norway, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, North America, and New Zealand and Australia. For each case study he clearly describes each project's details, aided by numerous illustrations: photographs of the completed buildings, construction photographs, floor plans, detail drawings, and diagrams. Too many books limit themselves to the first (glossy photos of finished buildings), so Solid Wood is a valuable book for architects interested in designing with wood.

Before delving into five of the buildings in the book designed by World-Architects member firms, it is worth pointing out what the "wood" in "designing with wood" is. It is not light-frame construction, which is common for single-family houses, but which has drawbacks that restrict if from being used in taller and more urban projects. It can be solid timber construction, such as logs, but more often it is engineered wood, in which small dimensional lumber is assembled with adhesives and pressure to create products with longer spans, a wider range of design options, and less variability than the individual lumber. These include glue-laminated timber (glulam), laminated veneer lumber (LVL), and cross-laminated timber (CLT). Given that these are the most popular systems being used today, the below case studies use these abbreviations, though other systems will be defined when necessary.

Helen & Hard

Pulpit Rock Mountain Lodge

Strand, Norway

Helen & Hard: Pulpit Rock Mountain Lodge (Photo: Erieta Attali)

Mayo told me that he selected projects that have different way of doing things. They are not just CLT or glulam; they exhibit the adaptability and flexibility of wood while responding to unique problems. One standout is this three-story lodge that serves the Stavanger Trekking Association in Norway. Instead of CLT, glulam, or LVL, architects Helen & Hard used doweled wood panels parallel load-bearing shear walls. Mayo writes it "may be the most complex wood doweled building ever built."

Helen & Hard: Pulpit Rock Mountain Lodge (Photo: Erieta Attali)

As the name of the system implies, doweled panels are built with dowels rather than adhesive, putting them a notch above the more popular wood systems in environmental terms. Large format wood panels known as Holz100 were used for the lodge, and while they are similar to CLT, the lack of adhesives and the fact the panels were made in Norway at the time made them the more economical choice. A couple other projects in the book, including Mühlebachstrasse discussed below and the Woodcube by architekturagentur, use dowels rather than adhesives (and a seven-story building has been built in Austria with Holz100), but the Pulpit Rock Mountain Lodge is more complex formally and spatially, thanks to the use of diagonals.

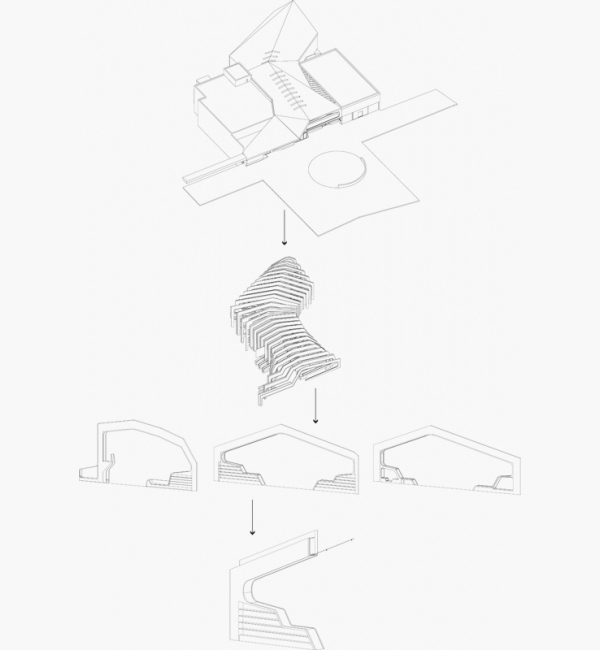

These diagonals are illustrated in the below diagram, which shows two conditions. On the far left is what results with the standard make up of the Holz100, which is, as shown to its right, alternating panels of diagonal (D), vertical (V), and horizontal (H), or HVDDVH. As the arrows show, the architects moved the diagonals to the outside to create a section of DDVHVDD, with the diagonal layers on the outside also holding the beams for extra stiffness and giving the space its defining characteristic. This is a project where design results from the synthesis of solid wood construction and technology, as good an illustration for what Mayo is doing with the book as any.

Helen & Hard: Pulpit Rock Mountain Lodge. "Levels of integration between architecture and structure." (Drawing: Helen & Hard)

Helen & Hard: Pulpit Rock Mountain Lodge. "Detail diagram of dowel laminated elements used in main gathering space." (Drawing: Helen & Hard)

Helen & Hard

Vennesla Library

Vennesla, Norway

Helen & Hard: Vennesla Library (Photo: Emile Ashley)

Yet the Pulpit Rock Mountain Lodge is not the only Helen & Hard project in the book; it is followed by the Vennesla Library, completed a few years later in Vennesla, Norway. A similar parti of repeating ribs is found in the library, but here executed in glulam rather than doweled panels. Most interesting, as Mayo told me, is that there are 27 unique sectional shapes in the building, which reveals the adaptability and formal expression available with wood.

Helen & Hard: Vennesla Library (Photo: Emile Ashley)

The wood ribs are actually made of glulam timber and CNC fabricated plywood panels, the former serving as the primary structure and the latter creating the enclosure for integrated ducts. Given that the ribs are lighting, mechanical, and book storage, not just structure, it was necessary to integrate two wood systems—three if we count the CLT floors and cross walls between the ribs.

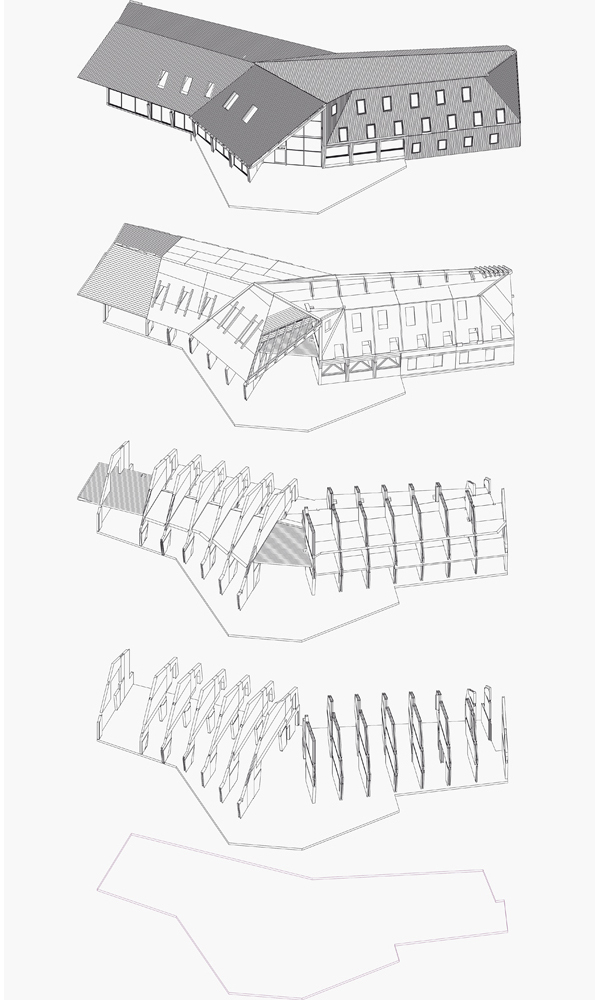

Helen & Hard: Vennesla Library. Exploded axonometric of building structure. (Drawing: Helen & Hard)

Architekten Hermann Kaufmann

LCT ONE

Dornbirn, Austria

Architekten Hermann Kaufmann: LCT ONE (Photo: Büro Kaufmann - AL)

One of the more well known and frequently published projects in Solid Wood is Life Cycle Tower One designed by Hermann Kaufmann. Mayo met with the engineers (Merz Kley Partner), who told him they decided to use glulam rather than CLT so the wood grains were in the proper direction for transferring loads. With 30-foot (9-meter) spans needed, the engineers combined the glulam with precast concrete planks. This hybrid mix performs exceptionally well in terms of acoustics, thermal mass, and fire rating, among other considerations.

Architekten Hermann Kaufmann: LCT ONE (Photo: Norman A. Müller)

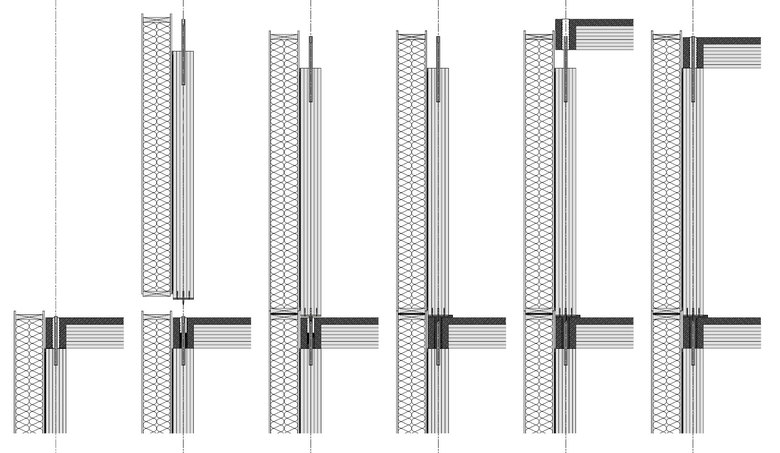

LCT ONE is not the only hybrid project in the book, and during our conversation Mayo seems to be in favor of hybrids when necessary, be it to work with conservative building codes or to build taller; the point is, he says, to use each material as efficiently and intelligently as possible. An obvious expression of these qualities in LCT ONE is found in the kit of parts system that could be applied just about anywhere (even to seismic zones like California): exterior prefabricated wall panels are slotted into the floor and adjacent wall panels, then grouted together for a speedy construction.

Architekten Hermann Kaufmann: LCT ONE. Section detail showing sequencing of floor and wall installation. (Drawing: Architekten Hermann Kaufmann)

Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architekten

Salzburg University of Applied Sciences Kuchl Campus Extension

Kuchl, Austria

Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architekten: Salzburg University of Applied Sciences Kuchl Campus Extension (Photo: Bruno Klomfar)

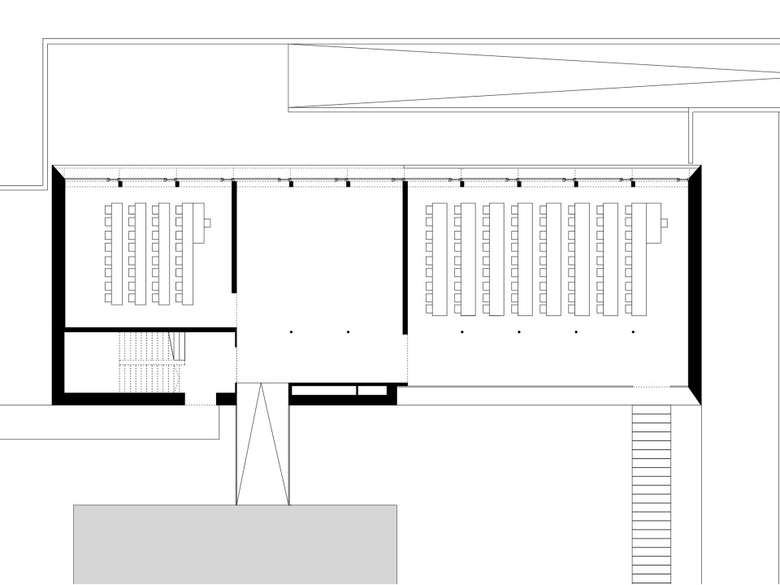

The choice of whether to build in solid wood versus concrete, steel or some other material is surely made easier when it is in the client's interest to build with wood. Such is the case with Salzburg University of Applied Sciences in Austria, which specializes in timber engineering. Even with a dedicated interest in timber construction, it was necessary to go the hybrid route, using concrete walls for the stair cores, which needed to be noncombustible construction, and steel beams to minimize the size of the structure in the classrooms.

Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architekten: Salzburg University of Applied Sciences Kuchl Campus Extension (Photo: Bruno Klomfar)

The building's end walls are solid to keep the envelope as tight as possible, so these were built from huge, three-story CLT walls panels. Elsewhere, glulam columns and beams were used in combination with steel connectors. Steel posts were also used, visible in the row of small circular columns in the first floor plan below. This extension to the school's Kuchl campus is another case where each material – wood, steel, concrete – is used efficiently, intelligently and in the right place, depending on the various considerations.

Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architekten: Salzburg University of Applied Sciences Kuchl Campus Extension. Ground floor plan. (Drawing: Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architekten)

Kämpfen für Architektur AG

Residential and commercial buildings Mühlebachstrasse

Zürich, Switzerland

Kämpfen für Architektur AG: Residential and commercial buildings Mühlebachstrasse (Photo: R. Rötheli)

The last of the five projects highlighted here is the most urban, situated in the center of Zürich. It is made up of two six-story buildings, one residential and one commercial, that look at each other across a shared courtyard. Stair and elevator cores were constructed from concrete and the exterior walls were made from prefabricated timber panels with glulam and LVL pieces. But most exceptional are the floors, which are a prefabricated composite wood and concrete system that results in higher ceilings than wood-only floors. This hybrid system enabled the elimination of the steel reinforcing typical of concrete floors, thereby eliminating the embodied energy that comes with the manufacturing of steel.