'Image Building' at the Parrish Art Museum

Image Building: How Photography Transforms Architecture — now on display at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York, from 18 March to 17 June 2018 — presents dozens of photographs by famous artists and architectural photographers. Editor in Chief John Hill walked through the exhibition with curator Therese Lichtenstein and filed this report.

Architecture is spatial and therefore the most experiential of the arts. A visit to a building is necessary to fully understand it. Yet most people learn about and appreciate buildings through the two-dimensional medium of photography. In response, a number of exhibitions in recent years have explored the intimate and long (the oldest surviving photograph, taken ca. 1826, is of buildings) relationship between architecture and photography. In late 2013, the J. Paul Getty Museum opened In Focus: Architecture, on the "interdependent relationship between photography and architecture," and one year later the Barbican exhibited Constructing Worlds, which "looked beyond the medium’s ability to simply document the built world." Add Image Building to this small but growing list. Fittingly, guest curator Therese Lichtenstein was inspired by a building — the Herzog & de Meuron-designed venue — to mount an exhibition that "explores the many connections found among viewer, photographer, and architect, from the 1930s to the present."

Image Building occupies three galleries and part of the central corridor at Parrish and is organized into three sections: Public Places, Cityscapes, and Domestic Spaces. Lichtenstein explained to me during a walk through the exhibition that they are "loose categories to jump off of and to sort of move against and even interrupt." With 57 photographs spread across the four spaces, placement is everything. For instance, James Casebere's Landscape with Houses (Dutchess County, NY) #2 from 2009 depicts domestic spaces but is located in the Public Places section (above photo), adjacent to Thomas Demand's Modell from 2000, whose subject is a parking garage. But both images capture models, scale buildings constructed by the artists and then photographed. Their relationship to each other is more important than any distinctions between the three categories.

One of the first photographs encountered, at an entrance to the Public Places gallery, is Thomas Ruff's 2001 photo of a portion of the Weissenhofsiedlung Stuttgart from 1927. His blurry image runs counter to the way photography was used at the time to depict the crisp, clean lines and unadorned surfaces of early Modernism. It also readies the museumgoer for the rest of the exhibition, in how it is populated primarily by artists photographing buildings rather than by the work of architectural photographers. The distinction is found in intent, as architectural photographers are usually hired by architects or clients to depict their buildings in the most flattering ways, while artists use the subject of architecture to explore meaning. Though artists outweigh the architectural photographers in Image Building, the two groups are united by the medium of photography and its defining characteristics: light, framing, color (or lack thereof), and focus. The last is evident in Ruff's w.h.s. 10 and elsewhere in the exhibition.

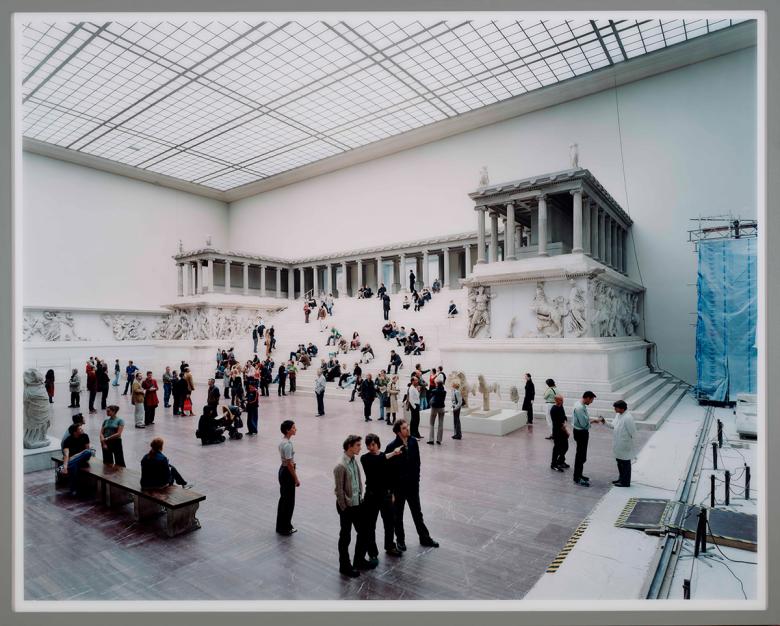

Also uniting the artists and architectural photographers in Image Building is a predominant lack of people; the number of photos in the show with people can be counted on one hand. This is not surprising in architectural photography, where the focus is squarely on the building: its form, surfaces, materials, and details. Iwan Baan, with his journalistic approach, is a notable exception, but even his trio of photos in the exhibition are devoid of people. For artists, the reasoning behind the same is more varied, but it makes the few photographs in the show with people that much more powerful. The solitary figure in Robert Adams' Colorado Springs, Colorado from 1968 is a case in point, as is Thomas Struth's packed Pergamon Museum I, Berlin from 2001. Although his photograph looks spontaneous, Lichtenstein told me Struth staged the people in the gallery and on the steps of the reconstructed Pergamon Altar. A close study of the large photograph in the Public Places gallery reveals the masterful balance of people and the way they lead our eye to certain parts of the image, such as the restoration work being done beyond the right edge of the frame.

Populated with photographs by Berenice Abbott, Samuel H. Gottscho, Ezra Stoller, and Hiroshi Sugimoto, among others, the Cityscapes gallery features a lot of images of Manhattan. Ranging in time from Abbott's and Gottscho's depictions of the metropolis in the 1930s to Iwan Baan's iconic photograph of a darkened Manhattan right after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the photographs document the changing city. They also, in the case of the grouped pairs seen here, reveal how photography has changed over that time and how the city has remained a canvas for artists to explore certain themes. For Sugimoto, his series of blurry photos of architectural icons depicts "architecture after the end of the world." Lichtenstein described his photos to me as "like a memory trace, like dream images." His photos also counter the notion, as famously stated by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, that "God is in the details." While important to architects, the details are ultimately subservient to the essence that is grasped through form — in our memories or with a camera whose focus is set to twice-infinity.

Most of the photographs in Image Building were taken on film, such as with Sugimoto's reliance upon old large-format, bellows-style camera. But digital technology is there, in the stitching of Andreas Gursky's large photo collages and in such pieces as Iwan Baan's The City and the Storm. Unlike the cityscapes of Abbot and Gottscho decades earlier with tripods and long exposures, Baan needed the latest in technology to capture a darkened Manhattan from a vibrating helicopter. As Lichtenstein details in the companion book to Image Building, he used "a highly sensitive camera": a Canon ID X camera with a 24-70mm lens on full open aperture, set at 25,000 ISO, with a shutter speed of 1/40 of a second. At four feet wide and six feet tall, seeing Baan's photo in person is one highlight of a show with many of them.

Just as Lichtenstein sets up comparisons between buildings in the Cityscapes section, she does something similar in Domestic Spaces, which moves outside of New York City to primarily other parts of the United States. But instead of explicit comparisons between specific buildings, we find ourselves returning to the artist/architectural photographer dichotomy. The latter is expressed best in the photos of Julius Shulman, who shot California's modern residential architecture but also captured the idealized lifestyles that went along with it. His iconic Case Study House No. 22 (Los Angeles, Calif.) from 1960, with its two carefully placed models, conveys so much more than just Pierre Koenig's architectural design.

On the other hand, Robert Adams' photos of suburban Colorado in the late 1960s and early 1970s and photos from Lewis Baltz's The Tract Houses portfolio from 1971 show a grim reality: of uninhabited houses and depressing landscapes. Although impoverished rather than utopian, Lichtenstein finds in Baltz's photos "a stark, intense minimal beauty to them." Their inclusion — and those of other photos of non-capital-A architecture — enriches the show, by asking visitors to fully consider photography's role in how we understand the built environment, and to examine, side by side, the many ways buildings are captured through images.

Image Building: How Photography Transforms Architecture is on display at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York, from 18 March to 17 June 2018.