How Allied Works Works

John Hill

23. outubro 2017

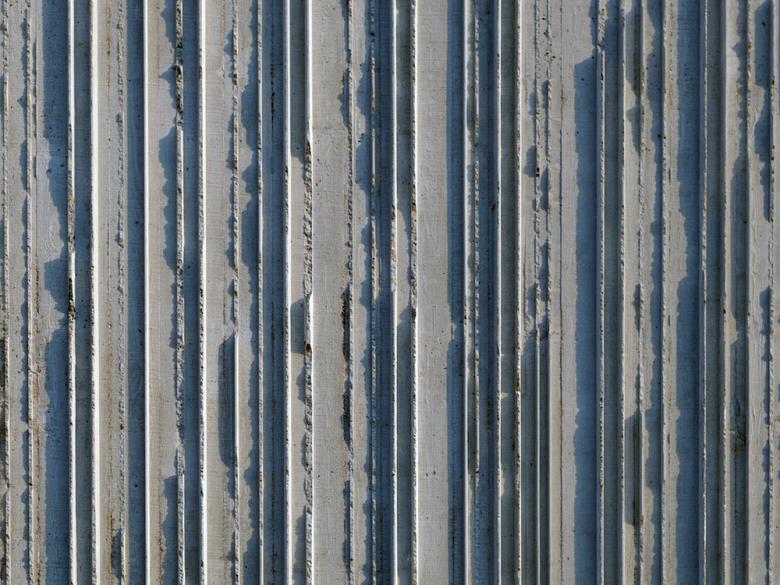

Facade detail of the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, Colorado, 2011 (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Allied Works Architecture is responsible for numerous notable museums, such as the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver, and institutional projects. But how does the firm work? How do Brad Cloepfil and his team develop such distinctive designs?

Cloepfil gave a keynote last month at the Vectorworks Design Summit in Baltimore, for which World-Architects served as media partner, and earlier this month at New York's The Cooper Union, where he holds the Ellen and Sidney Feltman Chair. Each talk was similar, covering mostly the same projects and highlighting the unique process that he and his colleagues at Allied Works employ. Founded in 1994, after Cloepfil earned degrees at the University of Oregon and Columbia University, Allied Works now has around 40 employees in two offices, in Portland and New York. Here we highlight the process of the firm as garnered through the two recent talks.

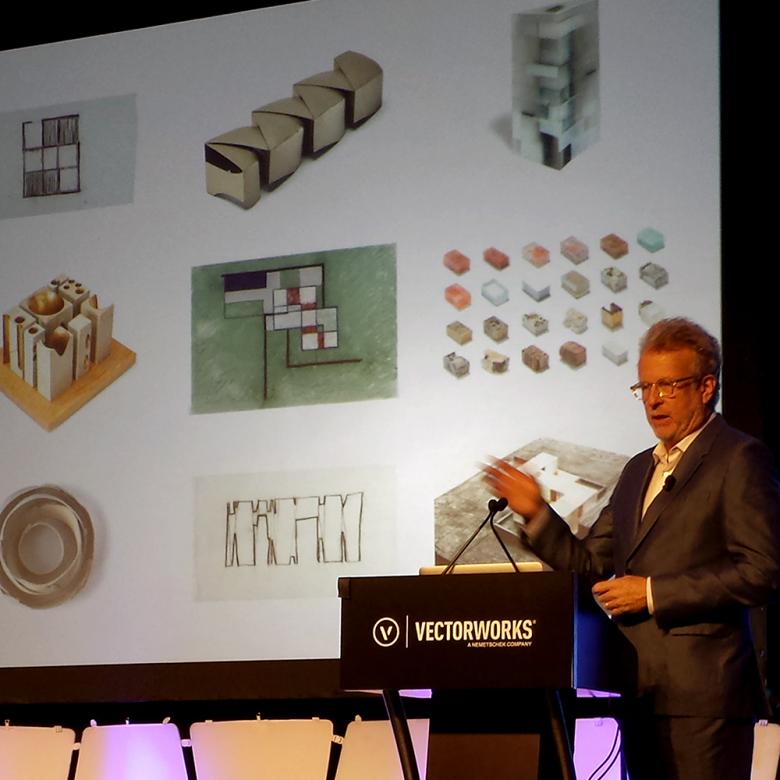

A slide with sketches and concept models: Brad Cloepfil during a keynote at the Vectorworks Design Summit 2017 (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The references that Cloepfil made in each talk were rooted more in the world of art than architecture. In his words, "I look at a lot of art for inspiration, for technique, for how [artists] visualize and how they think. For Allied Works, we look at any means possible to find the idea, to express the ideas." Such reference points as Richard Serra, Sol LeWitt and Julie Mehretu extend to the firm's concept models: "Looking for ways to visualize ideas, we use any media possible, from glass to steel to porcelain." With a traveling exhibition focused on the firm's process, Case Work: Studies in Form Space and Construction, their work can be considered art in and of itself, particularly the beautiful study models.

A view of the Case Work exhibition: Brad Cloepfil during a keynote at the Vectorworks Design Summit 2017 (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

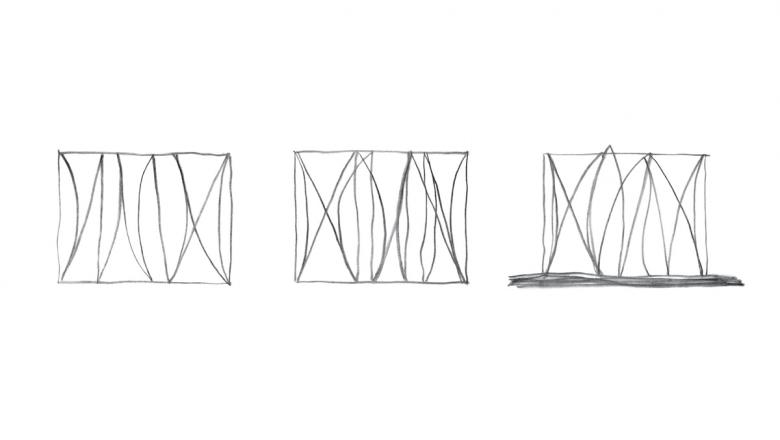

For Cloepfil, each project starts with charcoal drawings. This technique is rooted in his education all the way back to high school, where he took drafting classes and learned to draw by hand. Professors at the University of Oregon were influenced by Louis I. Kahn and therefore promoted that master's rough charcoal sketches, a technique that stuck with Cloepfil. He draws primarily in plan and section – "I can’t draw in perspective to save my life" – and then relies on his colleagues to take them to the next, three-dimensional level. A project for a guest house in Upstate New York began with a response to the "magical context" of the 350-acre site's deciduous forest. His initial drawing depicted a line weaving itself through the trees.

Brad Cloepfil's sketch of Dutchess County Residence Guest House (Image: Allied Works)

His drawing then led to this concept model in steel:

Study model for Dutchess County Residence Guest House (Image: Allied Works)

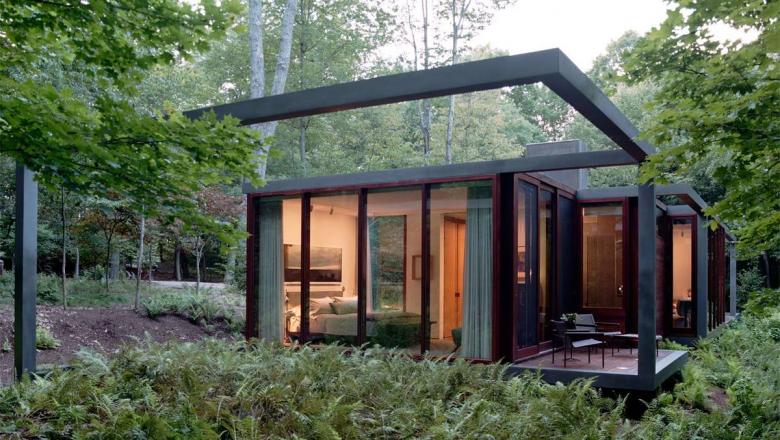

The final product, executed in 8-inch steel tubes, is in keeping with the concept as expressed in both drawing and model form. Enclosed rooms alternate with outdoor spaces framed by the steel, spaces where the landscape melds with its surroundings.

Completed Dutchess County Residence Guest House (Photo © Dean Kaufman)

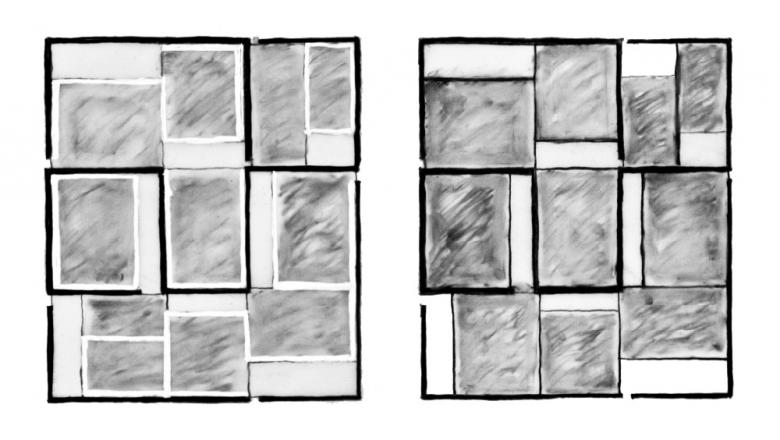

To date the most famous Allied Works project is the Clyfford Still Museum, completed in 2011 in Denver, Colorado, next door to Daniel Libeskind's addition to the Denver Art Museum. The concrete box of the Clyfford Still Museum is a quiet foil to Libeskind's aggressive building; it is an introverted building, blocking out this and the rest of its context. With Denver's location on the prairie just west of Rocky Mountains enabling it to be graced with sunlight 300 days out of the year, Cloepfil wanted to "bring light down to the surface" of Still's paintings. His nine-square plan sketches indicate a series of interlocking rooms, their continuous dark lines (walls) recalling the guest house in Upstate New York.

Brad Cloepfil's sketch for the Clyfford Still Museum (Image: Allied Works)

A concept model made from a piece of leftover timber from the basement of the Portland office reveals the museum's boxy volume embedded through a grove of trees, so "visitors would find the building through the landscape." As the street trees to the west and the grove of trees in the garden to the north fill out, the effect of this model should eventually be achieved.

Study model for Clyfford Still Museum (Image: Allied Works)

With trees adjacent to the building on two sides and neighboring buildings enclosing the other two sides, the natural light that Cloepfil desired had to come from above. Working with the lighting designers at Arup, Allied Works postitioned rows of skylights over a cast-in-place, perforated concrete ceiling. The natural light filtering through the ceiling is visible above the stair adjacent to the lobby, drawing visitors to the galleries on the top floor.

Outside, Denver's abundant daylight is celebrated through the texture of the cast-in-place concrete walls, as seen in the photo at top. Executed during a recession and with a "concrete contractor who had nothing to do," Cloepfil and his team experimented with the concrete mix and its formwork, even going so far as to use shag carpet for the latter. The main goal was "placing the concrete in a way that we couldn't control the outcome." This resulted in boards with gaps where the liquid would pass through and break off as the formwork was removed – a random yet controlled effect that fits well with Still's abstract paintings.

Interior of completed Clyfford Still Museum (Photo © Jeremy Bitterman)

Cloepfil described their design for the National Music Centre of Canada, completed last year in Calgary's East Village area, as "a portal to a neighborhood that is working and redeveloping." Given that their given site was made up of two properties on either side of a street, it's fitting that the building literally bridges the street to form a gateway. Cloepfil's early drawing merely hints at the building's organization as a series of nine interlocking towers as an armature for the project's museum, performance hall, interactive music education center, recording studio and broadcast center.

Brad Cloepfil's sketch for National Music Centre of Canada (Image: Allied Works)

With a varied program, the firm was developing concept models showing five-story towers, each with its own quality of light. Seeing them as too architectural too early, Cloepfil asked the interns in his office, "Why can't we go get a musical instrument, and just cut it up?" They took him at his word and cut up a trombone, cast it and milled it to create what Cloepfil considered "one of the most extraordinary things."

Study model for National Music Centre of Canada (Photo © Jeremy Bittermann)

Study model for National Music Centre of Canada (Photo © Jeremy Bittermann)

A later laminated wood model "in this process of exploration" picked up on the ideas embedded within that concept model, fitting it into the two-parcel site but also tying the volumes together that would lead to "an autonomous experience." Eventually these models, by way of digital models in Vectorworks and other software, led to a complex structure with equally complex interstitial spaces for circulation between the program elements. Custom glazed terracotta tiles, inside and out, subtly echo the metallic surfaces of the cut-up trombone, a vestige of sorts from the concept model.

Interior of completed National Music Centre of Canada (Photo © Brandon Wallis)

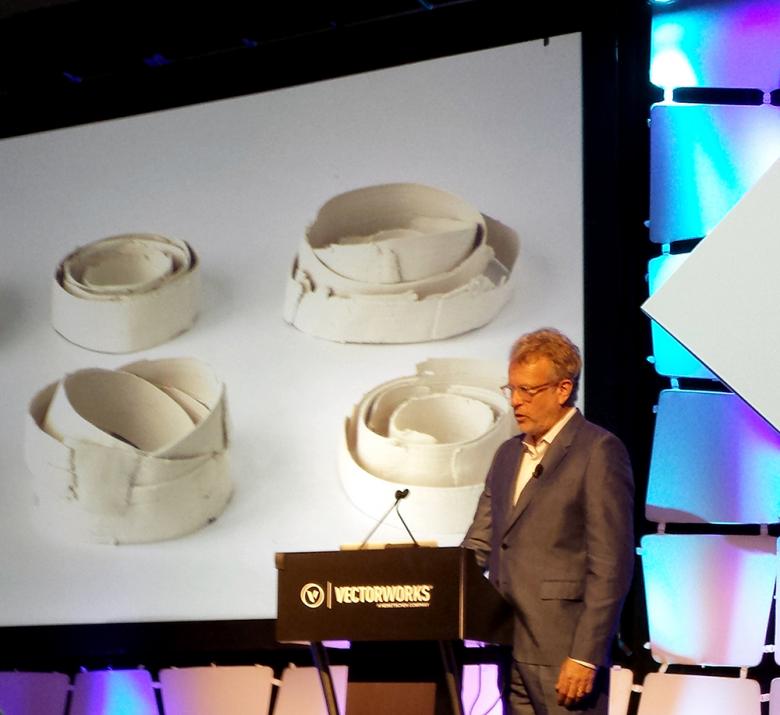

A project nearing completion that promises to bring more attention to Allied Works, surpassing that of the Clyfford Still Museum, is the National Veterans Memorial and Museum in Columbus, Ohio. Spearheaded by the late Senator John Glenn, the new institution "uses the military as a platform ... but really talks about the idea of service, the idea of doing something for others" in Cloepfil's words. With programming and exhibition design by Ralph Appelbaum Associates, Allied Works focused on expressing the project's main idea and the building's relationship to its context. Early models in porcelain explored the small building's presence on its large site.

Study models for National Veterans Memorial and Museum: Brad Cloepfil during a keynote at the Vectorworks Design Summit 2017 (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

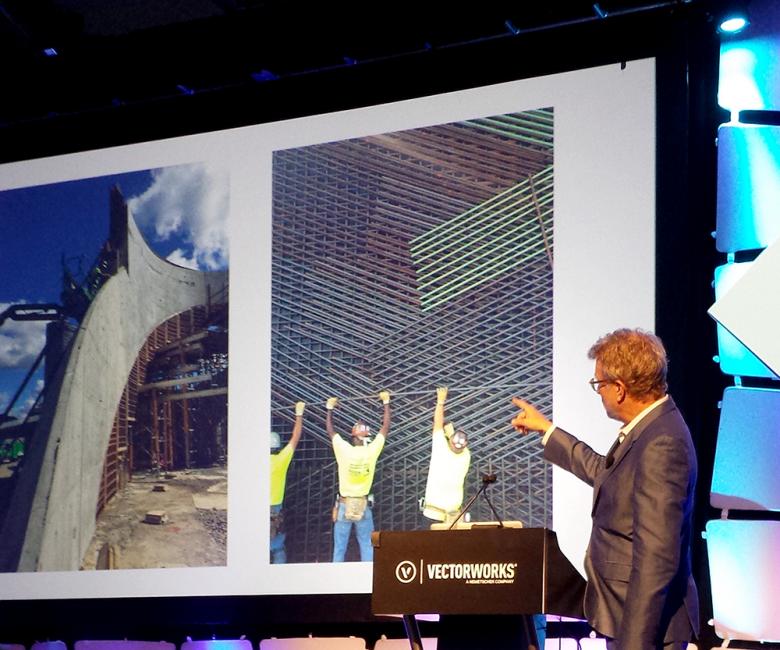

Their final design combines landscape and building in a spiraling composition supported by cantilevered concrete arches. This complicated approach involved numerous engineers and contractors, some of them too timid to take on the challenge.

National Veterans Memorial and Museum (Image: Allied Works)

With up to eleven layers of reinforcing embedded within the three rows of concentric concrete walls, Cloepfil described the National Veterans Memorial and Museum as a textile building. When I spoke one on one with Cloepfil after the Vectorworks keynote and asked him if this project signaled a new direction for the firm, he said, "I don't want to do that stuff forever. We were in the finals for a number of competitions where we lost to boxes. We were doing things that were more interwoven but not as complex as the National Music Centre or Veterans Memorial."

National Veterans Memorial and Museum under construction: Brad Cloepfil during a keynote at the Vectorworks Design Summit 2017 (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

While these words might point to a future filled with more Clyfford Still-like boxes, which look inexpensive but aren't, the firm's most recent projects – particularly the restaurant at Eleven Madison Park and Providence Park Stadium Expansion – indicate the work of Allied Works is highly varied and unpredictable – rooted in a process that prioritizes ideas and the exploration of form.