US Building of the Week

Walker Hall

Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects

17. abril 2023

Photo: Bruce Damonte

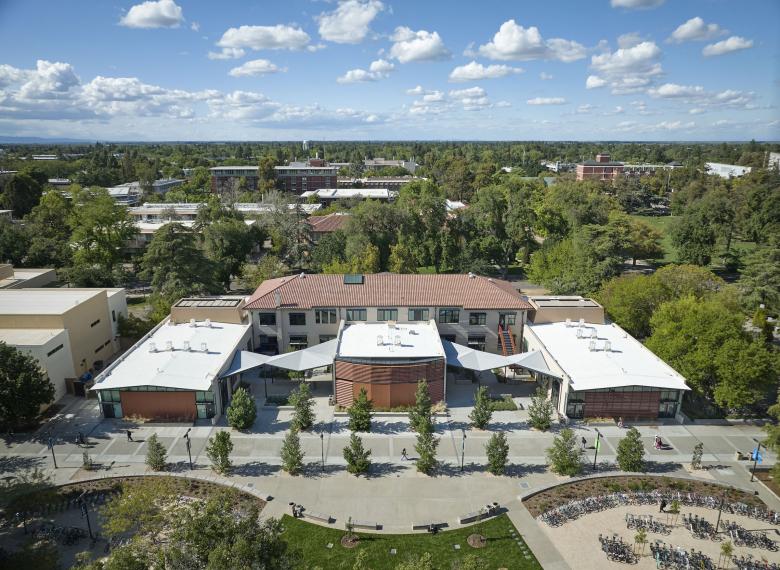

Walker Hall is the adaptive reuse of a nearly century-old building on the campus of the University of California, Davis, transforming it from a home for agricultural engineering to a student center, “a hub of university life.” The architects at Leddy Maytum Stacy answered a few questions about the project.

Location: Davis, California, USA

Client: University of California, Davis

Architect: Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects

- Design Principal: Bill Leddy

- Project Architect: Jasen Bohlander

- Project Manager: Ryan Jang

- Project Team: Alice Kao, Enrique Sanchez

Civil Engineer: BKF

MEP/FP Engineer: Arup

Landscape Architect: The Office of Cheryl Barton

Lighting Designer: ALD

Security / Low Voltage / Acoustical: Charles Salter

AV: Shalleck Collaborative

Cost Estimating: TBD Consultants

Specifications: Stansen Specs

Building Area: 34,000 sf

Photo: Bruce Damonte

Please provide an overview of the project.Walker Hall is an adaptive reuse of a 1927 building at the core of the University of California, Davis campus. The project transformed a vacant, seismically unsafe building into a graduate and professional student center with meeting rooms, a lecture hall, and sophisticated active-learning classrooms that serve the entire campus. It coalesces history, community, and advanced educational environments at a hub of university life.

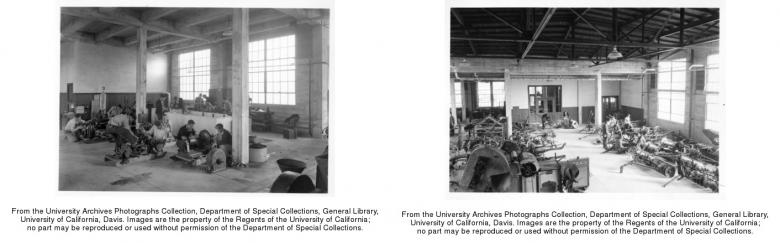

The original 34,000-square-foot building, designed to house the university’s growing agricultural engineering program, was one of the earliest buildings on campus. Its two-story Spanish-style wing faces north to the central quad and housed classrooms and offices. To the south, three lofty, clear-span wings served as large shops for hands-on research, design, and fabrication of farming machinery.

Photo: Bruce Damonte

The revitalized building is an important addition to the university’s graduate and postgraduate programs, which account for only 20% of the total student body. It supports graduate students’ academic, professional, and personal well-being with rooms for mentoring and advising as well as financial and mental health counseling. A variety of social, meeting, and study spaces foster collaborative, interdisciplinary discourse and help students build a strong scholarly community. The two-story north wing houses a graduate student lounge, counseling rooms, studies, multipurpose meeting spaces, and administrative offices. We shortened the three southern wings to allow for a new campus walkway and repurposed the three shop wings as a two-hundred-seat lecture hall and two large general assignment classrooms. These spaces are flexible active-learning environments that incorporate sophisticated media and digital technologies. In this way, the former machine shops now offer a new kind of toolbox that supports contemporary action-based learning.

Photo: Bruce Damonte

What are the main ideas and inspirations influencing the design of the building?Walker Hall illustrates how an unsafe, abandoned structure can be transformed into a sophisticated educational and administrative environment for a major university.

Over twenty workshop and design meetings were conducted during the design phases with diverse stakeholders, including university administration, faculty, graduate students, and facility maintenance personnel. Each of these participants represented larger constituencies identified by the university to ensure the broadest possible engagement. With the demographics of the student body already one of the most diverse in the nation, the project goals of Walker Hall were to support inclusion and build a stronger academic community. These goals were established by the university and project stakeholders at the onset of the process.

Photo: Bruce Damonte

How does the design respond to the unique qualities of the site?“Now one of our oldest buildings is one of our most innovative.” – Chancellor Gary May.

The idea that the old can be innovative is at the core of Walker Hall. By choosing adaptive reuse in lieu of demolition and new construction, Walker Hall illustrates how an existing structure can be given new life while preserving both its embodied carbon and embodied culture. The design is anchored in the unique characteristics of its place – its rich academic history and hot, dry climate.

Photo: Bruce Damonte

The design is anchored in the unique characteristics of its place — its rich academic history and hot, dry climate — welcoming a diverse student body at the core of campus life. The design team worked carefully to preserve as much of the existing concrete, steel, and wood structure as possible, reducing carbon emissions and celebrating the agricultural engineering legacy of the building and the university. Existing steel trusses, concrete columns, and finishes are retained and celebrated. High-performance modern facades are inserted within the original shells of the shop wings, expressing new academic uses to a revitalized campus promenade. Interior learning spaces open to the promenade through shaded windows that display academic life within during the day and glow like giant lanterns after dark.

Photo: Richard Barnes

New exterior details—steel sunshades, cylindrical daylight collectors, a sculptural steel stair, and geometrically folded shade canopies—speak to the industrial past of the building. Walker Hall received a combined deep-energy and seismic retrofit, with new energy-efficient building systems and envelope upgrades. These improvements have extended the life of the structure for another 100 years, radically reducing energy use and operational carbon emissions. Actual energy performance in the first year of full occupancy has been 80% below baseline including renewable energy contributed by an on-campus solar farm. New thermal insulation and high-efficiency building systems, combined with dedicated renewable energy provided by an on-campus solar farm will result in a zero net electricity building.

Photo: Richard Barnes

How did the project change between the initial design stage and the completion of the building?The original university-mandated project sustainability goal was LEED Gold certification on a modest budget. Through the careful integration of the simple, cost-effective strategies described herein, Walker Hall ultimately achieved LEED Platinum certification at no additional cost, while also saving over 700 metric tons of CO2 emissions — a 57% reduction — when compared to building a new structure.

Twenty-one months of post occupancy energy data is available to compare against design-phase energy models. The model targeted an EUI of 83 kBtuh/sf/yr representing a modest 37% reduction from a baseline EUI of 132. Actual EUI without renewable energy contribution is 58: a 56% reduction. An on-campus PV “Solar Farm” offsets 100% of the building’s electrical needs and reduces the EUI to 37 — a 72% reduction exceeding the original 2030 Commitment goal. The design team and the university have collaborated since opening to optimize energy use and leverage unforeseen efficiencies, resulting in a further reduction of 80% below baseline.

Photo: Richard Barnes

Was the project influenced by any trends in energy-conservation, construction, or design?In response to the hot, dry climate of California’s Central Valley — projected to become even hotter and dryer in the future — potable water use reduction was a key design strategy for Walker Hall. Ultra-low-flow toilets and urinals are used throughout the project, and each sink fixture is fitted with a specialized aerator to further reduce water use, resulting in a 40% reduction in potable water use from the baseline for university buildings. At the building exterior, native drought-tolerant planting is used to reduce irrigation water by 59%. Once selected native plants are established, irrigation will be further reduced. Adjacent to the pedestrian promenade is a highly visible and lushly planted bio-filtration ponds with integrated seating to which hardscape and roof runoff is routed. Filtered stormwater is then routed to subgrade holding tanks where it is slowly fed into the campus stormwater system, which in turn feeds natural streams and ponds on campus that are home to native turtles, water birds, and insects.

Email interview conducted by John Hill.