David Geffen Hall Opens at Lincoln Center, Two Years Ahead of Schedule

John Hill

10. 十月 2022

Wu Tsai Theater inside David Geffen Hall (All photographs by John Hill/World-Architects unless noted otherwise)

David Geffen Hall, home to the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, opened its doors on October 8. World-Architects got a tour of the building's public spaces and acoustically improved theater.

Since it opened in 1962 as the first piece of the ambitious and controversial Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Philharmonic Hall was plagued by acoustics that could best be described as subpar. It was an inauspicious start for a decade-in-the-making project that displaced 20,000 residents, many of them from Puerto Rico, in the making of a cultural acropolis with facilities devoted to ballet, opera, symphonies, and theater.

The poor acoustics of Philharmonic Hall led to numerous renovations to the concert hall inside the building designed by Max Abramovitz. The first major one was carried out by Philip Johnson and completed in 1976, when the building was renamed Avery Fisher Hall. Minor tweaks followed but nothing helped bring the hall up to the level of great halls around the world, including the nearby Carnegie Hall that was home of the Philharmonic before the construction of Lincoln Center.

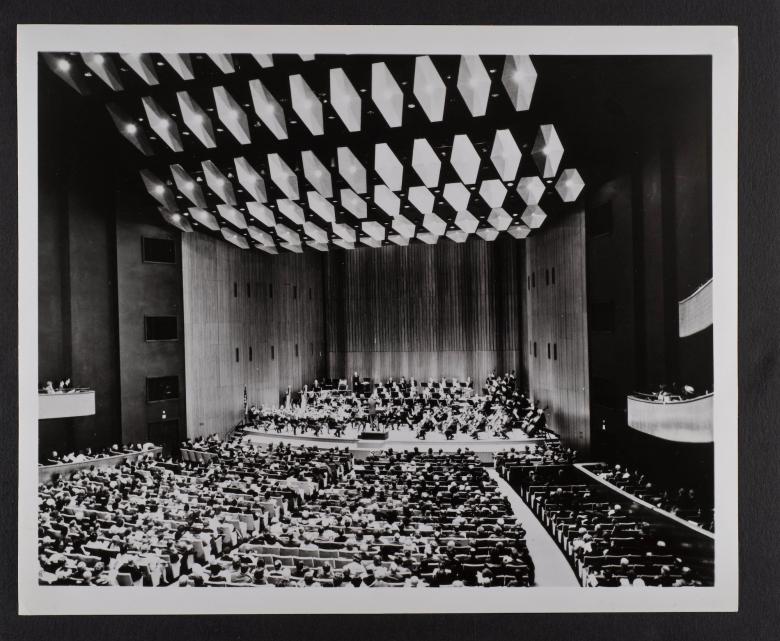

Historic photography of the then-Philharmonic Hall in 1964. (Photo courtesy of the New York Philharmonic Shelby White & Leon Levy Digital Archives)

In 2003, Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic, respectively landlord and tenant, explored tearing down the original building and replacing it with a competition-winning design by Norman Foster. Deemed too expensive and too time-consuming, the two players opted to carry out more minor tweaks instead — none doing the job of undoing the hall's problems. Then a $100 million donation by David Geffen in 2015 arrived as something of a godsend. That same year Heatherwick Studio and Diamond Schmitt Architects were hired to redesign the newly renamed David Geffen Hall, but their proposal came in costing double the anticipated $500 million budget, so the project was cancelled in 2017.

With the reset button pushed once again, but also having learned from numerous false starts, Lincoln Center and the Philharmonic pared down the project to a gut renovation of the theater and improvements to the lobby and other interior public spaces; the exterior would remain intact and nothing would be added to the top of the building. Diamond Schmitt, working with acoustical designer Akustiks, stayed on as designer of the theater, and Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects Partners (TWBTA) were brought in to design the public spaces. Planned to open in March 2024 when it was unveiled at the end of 2019, the timeline moved forward nearly two full years when the pandemic hit and concerts were suspended — one of the few upsides arising from the pandemic in New York City.

Historic photography of the then-Avery Fisher Hall in 1992. (Photo courtesy of the New York Philharmonic Shelby White & Leon Levy Digital Archives)

With the opening of the newly renovated $550 million David Geffen Hall on Saturday, October 8, the story of Philharmonic Hall came full circle: the Philharmonic debuted a piece composed by Etienne Charles, San Juan Hill: A New York Story, that acknowledges the complicated history of Lincoln Center. Additionally, the north facade of the building features a site-specific artwork by Nina Chanel Abney, San Juan Heal, that pays tribute to the residents displaced more than sixty years ago.

In line with contemporary calls for equity, diversity, and inclusion, the number of accessible spaces in the hall has been increased, even as the total number of seats was reduced (the large size of the hall was deemed an acoustic detriment). The lobby and other public spaces at Geffen Hall have also been improved with considerations toward people with limited mobility, from the car drop-off and movement through the building to the theater itself. The press tour of the building that World-Architects attended mainly moved through the public spaces, so the photos and captions that follow focus primarily on those areas.