11. 十月 2023

The Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms State Park at the time of its opening in October 2012. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Landscape architect Harriet Pattison, a collaborator of Louis Kahn and mother of his only son, died on October 2 at the age of 94; and Andrea Branzi, the designer and cofounder of Archizoom, died on October 9 at the age of 84.

Harriet Pattison (1928–2023)

Although Harriet Pattison designed the landscaping for one of Louis Kahn's masterpieces, the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, it took her son Nathaniel Kahn's 2003 documentary My Architect for her to be recognized by most architects. Still, within the context of a film about a son striving to learn about a father who had three children with three women, Pattison's role and abilities as a landscape architect remained in the shadow of her outsized partner's life and accomplishments. It is telling that, when Kahn and Pattison's shelved 1973 design for Four Freedoms Park, a memorial to Franklin Delano Roosevelt's “Four Freedoms” speech from 1941, was resurrected a few years after My Architect, Pattison was not consulted on the park that eventually opened on New York's Roosevelt Island in 2012. The landscape architect at Mitchell/Giurgola, the firm that consulted with Kahn in 1973 and completed the project decades later, is quoted in a New York Times obituary on Pattison as admitting "I never heard the name Harriet mentioned." (Even our brief headline on the park's opening in October 2012 failed to acknowledge Pattison.)

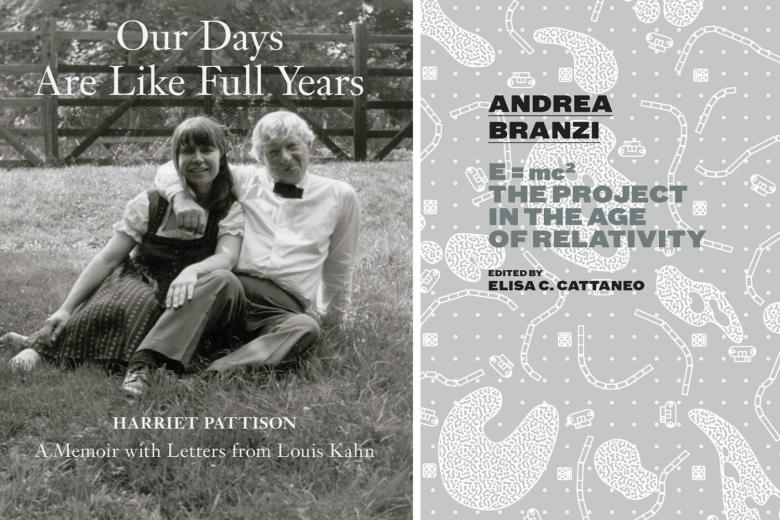

Pattison's 15-year relationship with Kahn, which lasted from 1959 to Kahn's death in 1974, was retold in her 2020 book Our Days Are Like Full Years: A Memoir with Letters from Louis Kahn. The book's fifteen chapters recount each of those years, one by one, with the last two focusing on the commission for Four Freedoms Park. “Lou made it clear that we would do this one together from the beginning,” she wrote about a project more landscape than building. A page on The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) website calls it “the culmination of their collaborative work.”

Born in Chicago on October 29, 1928, Pattison received a BA from the University of Chicago in 1951, later studied at Yale and the University of Edinburgh, and eventually settled in Philadelphia. There she was introduced to Kahn by a common friend, Robert Venturi, and in 1962 Nathaniel, her only child, was born. Soon after, she apprenticed in the office of landscape architect Dan Kiley and then studied landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania under Ian McHarg. After graduating in 1967, she worked in the office of landscape architect George Patton for a few years then collaborated with Kahn on the Kimbell, which opened in 1972. She opened her own office following Kahn's death in 1974 but continued to collaborate with Patton on occasion. Pattison was named a fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 2016.

Both Pattison and Branzi wrote biographical books that were released in 2020. (Photos: Yale University Press; Actar)

Andrea Branzi (1938–2023)

Andrea Branzi, alongside Gilberto Corretti, Paolo Deganello, and Massimo Morozzi, founded Archizoom in Florence in 1966, taking their name from the fourth issue — Zoom! — of Archigram's numbered zines. Although the radical group, which was soon joined by Dario and Lucia Bartolini, would stay together for just eight years, furniture they designed in the late 1960s remains in production, including the flexible Superonda sofa/bed/chaise and the modular Safari sofa. These Pop Art-inspired pieces designed for Poltronova merited the group's inclusion in the seminal 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) alongside the fellow Florentines in Superstudio and Gruppo 9999.

While Branzi is still recognized mainly for his role in Archizoom and the creation of such projects as No–Stop City, his subsequent career continued to explore experimentation in design, but instead of in Florence, where he was born and raised, it tool place in Milan, Italy's nexus of design, where he moved in 1973. He joined Studio Alchimia and Memphis Design Group, which were born in Milan in 1976 and 1980, respectively. He helped to set up the Domus Academy there in 1982, serving as its cultural director for a decade, and in 1988 he wrote Learning from Milan: Design and the Second Modernity, one of numerous books he authored.

“Branzi would devote his entire life to researching and experimenting with new idioms. Profoundly conscious of the link between design, manufacturing and social transformation, he believed in the fundamental importance of energy in the design process, regardless of whether or not the project ever came to fruition. He even went so far as to espouse the idea of experimental craft work, and of free, independent research workshops, more suited to small production runs than those that happened on an industrial scale.”

Branzi was lauded many times over his long career of designing, teaching, curating, and theorizing about cities, most notably multiple Compasso d'Oro, including one in 1987 for his career, and the Rolf Schock Prize in Visual Arts in 2018.